Please wait while flipbook is loading. For more related info, FAQs and issues please refer to DearFlip WordPress Flipbook Plugin Help documentation.

Tkanka malarstwa

Twórczość Krzysztofa Gliszczyńskiego jest kompletnie zanurzona w malarstwie. Artysta ten z przekonaniem, dociekliwością i namiętnością zapuszcza się w coraz głębsze jego rejony, eksplorując materialność farby nakładanej na płaszczyznę i nieustannie pytając o jej rolę i potencjał jako nieludzkiego aktora, biorącego aktywny udział w procesie tworzenia.

Na wczesnym etapie Gliszczyński mieszał z farbą mielony pył marmurowy, który daje wrażenie niesamowitej aksamitności faktury, uwodząc dotyk. Świetnym przykładem jest tutaj „Obiekt szary z urną nr 20 i 21” z roku 2000, w którym „nadmiarowe”, wydrapane z płaszczyzny elementy materii artysta umieścił w centrum niczym relikwie. Również o rok późniejszy obraz „Nigredo” emanuje matową, jakby welurową powierzchnią, a spod warstwy czerni mocno uwidacznia się intensywnie niebieski rysunek wykonany w materii farby. Najwcześniejszy prezentowany na wystawie w galerii SZOKART obraz „Palimpsest” z 1994 roku to olej, pył marmurowy i enkaustyka na płótnie, a owo nietypowe połączenie technik przyczynia się do powstawania efektu aksamitności i wielowarstwowości, na którą wskazuje sam tytuł – palimpsest to wszak rękopis spisany na używanym już wcześniej materiale piśmiennym, z którego usunięto poprzedni tekst.

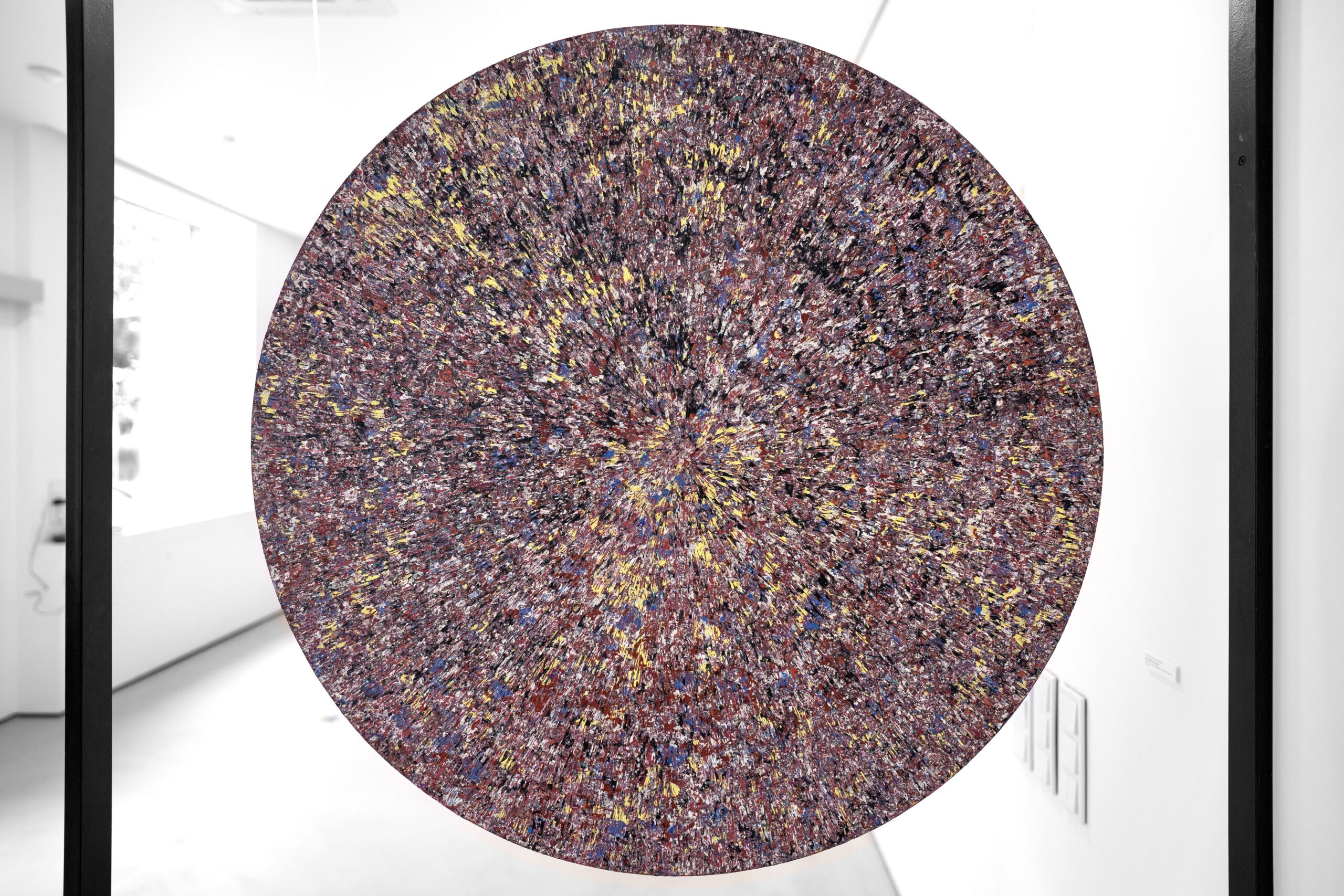

Pozostałe obrazy, m.in. te z cyklów „Pneuma”, „Perpetuum pictura” czy „Toledo” operują z kolei techniką enkaustyki – również bardzo haptyczną, ponieważ w jej ramach spoiwem jest wosk, który także kusi oko na koniuszku palca. Twórca zdaje się więc sugerować, że widzenie jest dotykaniem za pomocą wzroku. Nasz dotyk przywołują m.in. dwa tonda zatytułowane „Znikający punkt” (2008) czy „Nieoczywiste” (2009), których płaszczyzny mienią się intensywną kolorystyką i zdają się dynamicznie optycznie wirować.

Gliszczyński tworzy zatem haptyczną tkankę malarstwa, która apeluje nie tylko do zmysłu wzroku, lecz indaguje również nasz zmysł dotyku i cielesną percepcję. Ulubionym filozofem i teoretykiem malarstwa artysty jest francuski fenomenolog Maurice Merleau-Ponty, którego Gliszczyński czytuje od lat, z nieustającą fascynacją i skupieniem, by jego tezy przekładać na swój własny, oryginalny malarski język, co doskonale widać w obrazie z roku 2023 zatytułowanym „Lekcja malarstwa według Merleau-Ponty’ego”. Merleau-Ponty pisał: „Widzialne i ruchome, ciało moje zalicza się do rzeczy, jest jedną z nich; tkwi w tkance świata i jego spójność jest spójnością rzeczy. Jednakowoż, skoro widzi oraz się porusza, w krąg ustawia rzeczy wokół siebie, one zaś są jakąś jego dobudówką bądź też przedłużeniem, są inkrustowane w jego cielesności, stanowią część jego pełnej definicji i tworzywem świata jest tworzywo ciała.” Prace Gliszczyńskiego są inkrustowane w jego cielesności i podobnie jak jego malujące ciało tkwią w tkance świata, z którą są spójne. Parafrazując dalej słowa Merleau-Ponty’ego dodałabym, że rozprzestrzeniający się ruch ciała artysty w trakcie procesu tworzenia jest naturalnym następstwem, dojrzewaniem widzenia, prowadzącym w efekcie finalnym do rytmicznego zapisywania gestów na płótnach i papierach.

Moim zdaniem owe gesty zapisują się w formie owej tkanki świata, o której wspominał Merleau-Ponty. Gliszczyński przetłumaczył ją – jakże celnie – na tkankę malarstwa, która dochodzi do głosu szczególnie w ostatnich obrazach, które mają swoją premierę na wystawie w galerii SZOKART w Poznaniu. Jest w tych dziełach ucieleśniona tkankowość, gąbczastość, wilgotność, czy jakby lepkość. W „Studium do melancholii” z roku 2022 kontrast powierzchni gładkiej z tą wyżłobioną oraz czerwonawa kolorystyka nadają temu dziełu wyjątkowej intensywności.

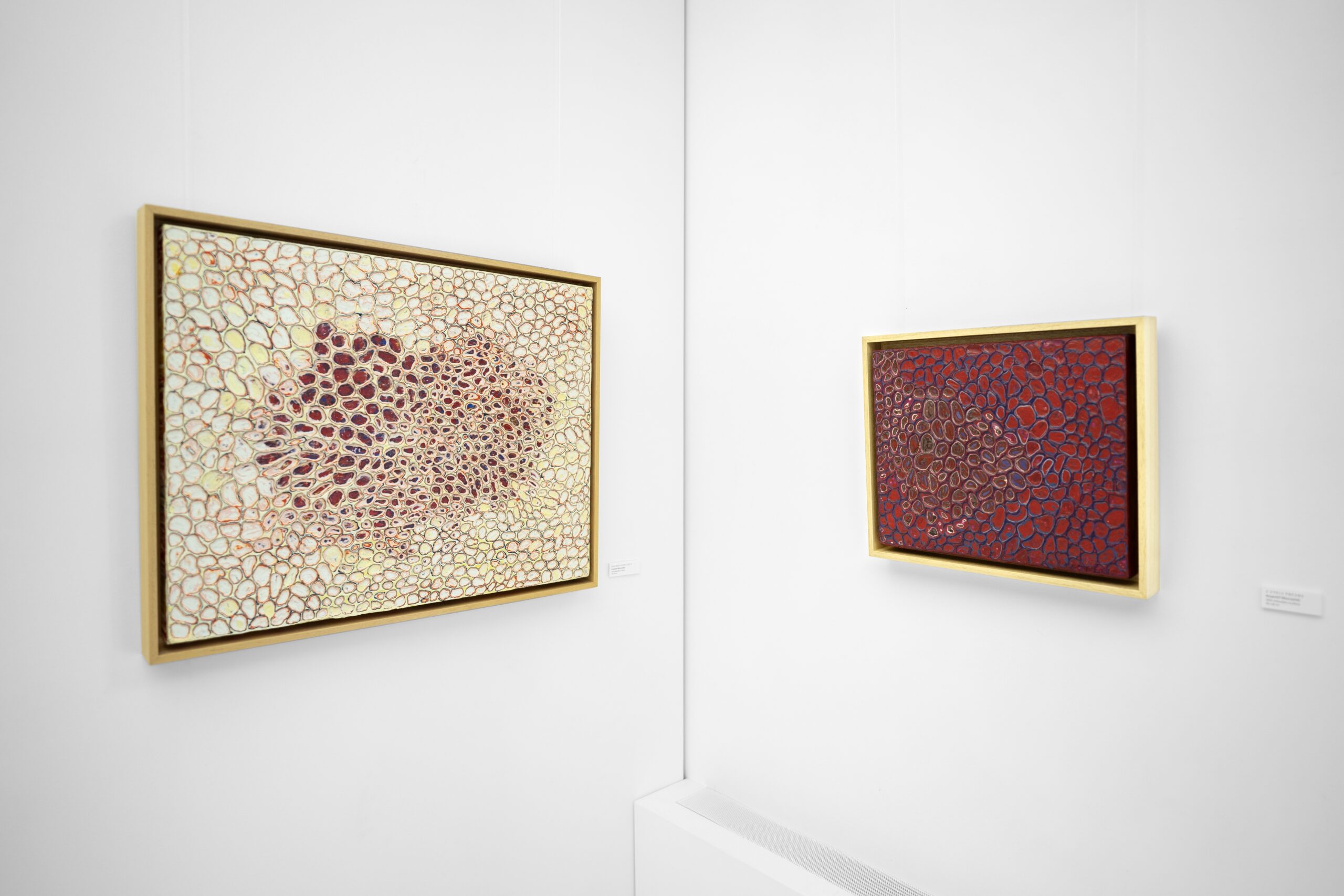

W wyniku żmudnego i precyzyjnego nanoszenia kolejnych warstw „tłustej” enkaustyki, powstającej na bazie podgrzanego wosku, wyłaniają się kompozycje mocno skondensowane i zagęszczone, dotykalne. Ich powierzchnie są żłobione, a w każdym wgłębieniu ujawnia się i odsłania – jak stratygrafia w ramach geologii – każda kolejna warstwa nałożonej wcześniej farby. W „Ukrytej historii” z roku 2024 na dole pozostał pas farby, w której artysta nie żłobił – czy to właśnie pod nią ukrywa się tytułowa historia? A może rozgrywa się ona bardziej w napięciu między żłobieniami a materią na dole, która nie odkryła swoich spodnich warstw? Wybrania farby sięgają głębiej lub płyciej: do bieli, żółci, niebieskości, które pobłyskują na tle dominującej czerwieni, nadając obrazowi dynamiki i intrygując nasze oczy na koniuszkach palców, którymi chcielibyśmy każdego z tych wgłębień dotknąć. Wszystkie obrazy w tej technice to struktury tętniące podskórnym życiem, które mają w sobie prostotę jednokomórkowców i siłę kolonii analogicznie zbudowanych organizmów, emanujących energią dzięki strategii ich multiplikowania. Ich istota w dużym stopniu zależy od taktyki, jaką Gliszczyński przyjął, by wybierać nadmiarową materię malarską.

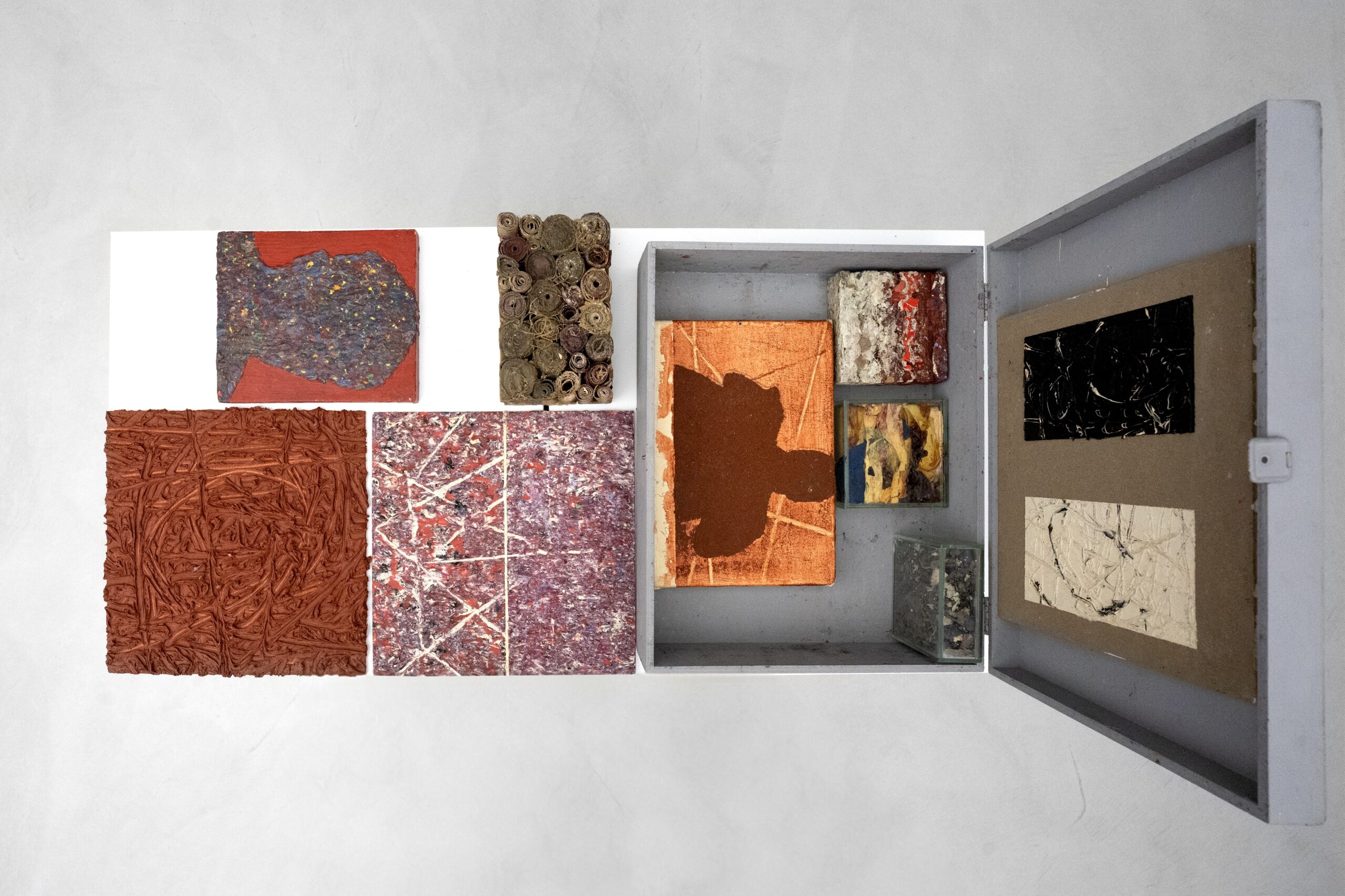

Formy rodzą się zatem dzięki ścisłej współpracy operatywnego ciała malarza, używanego narzędzia oraz jego styku z płaszczyzną. Artysta skrupulatnie dłubie i wydłubuje cząsteczki farby, lecz się z nimi nie rozstaje: zbiera je, umieszcza w pleksi, niczym relikty w urnie, i prezentuje jako część wybranych kompozycji jak np. w „Rozwarstwieniu” z cyklu „Pneuma” z roku 2023 czy „Perpetuum pictura 3” z roku 2020. Uzmysławia tym samym odbiorczyniom i odbiorcom swoich dzieł, że materia malarska krąży w procesie tworzenia, poddając się kształtowaniu na różne sposoby przez operatywne ciało twórcy. A owo ciało z czasem zyskuje i rozwija coś w rodzaju własnego stylu i pamięci mięśniowej, dzięki której może działać samodzielnie i automatycznie. „Pamięć mięśniowa to termin powszechnie używany w codziennym dyskursie na określenie swoistego rodzaju nieświadomej, ucieleśnionej pamięci, umożliwiającej nam, w nieuzmysłowiony sposób, wykonywanie pewnych czynności ruchowych, które opanowaliśmy wskutek przyzwyczajenia lub celowego ćwiczenia albo, po prostu, w wyniku nieformalnego, nieintencjonalnego lub wręcz nieświadomego uczenia się z wcześniejszych doświadczeń.” Patrząc na te obrazy, w wyobraźni „drążymy” je własnym ciałem i własną dłonią; odzywają się bowiem echa naszej własnej mięśniowej pamięci, która wirtualnie angażuje się w kreowanie tkanki malarstwa. Ucieleśniamy je w nas samych, przesuwając miękko wzrokiem po każdej kolejnej formie i napinając mięśnie, które pracowały(by) przy ich rzeczywistym kreowaniu. To formy, które sprawiają wrażenie samoprojektujących się, podążających za powtarzalnymi, precyzyjnymi gestami operatywnego ciała Gliszczyńskiego, który prowadzi narzędzia malarskie w taki sposób, by widzenie i ruch splotły się w jedno. W efekcie powstają struktury, które poniekąd same się kreują we współpracy z myślącą dłonią, przejmując inicjatywę i prowadząc dalej w procesie samokreacji. To ślady ciała, które – zyskując własną somatyczną i wizualną mądrość – rozprzestrzeniają się zachłannie i pozyskują coraz większą płaszczyznę, by móc się plastycznie wyłonić. Metoda pracy Gliszczyńskiego uruchamia bowiem zjawisko, które nazwałabym samokreowaniem się formy, jej „pączkowaniem”, w ramach którego podejmowane są wątki, ujawniające się w trakcie procesu tworzenia. Materializacja idei następuje zatem nie tylko wskutek przejęcia inicjatywy przez dłoń, trzymającą narzędzia malarskie i w końcu szpachlę, która usuwa nadmiar farby i drąży rytmiczne wgłębienia, lecz również w relacji do aktywności samej formy, którą to dynamikę artysta instynktownie i bez zawahania włącza w splot widzenia i ruchu.

Na taki rezultat i stan trzeba bardzo długo pracować – „wgryzać się” zarówno w tkankę świata, jak i w tkankę malarstwa: jednocześnie świadomie, jak i intuicyjnie, aktywując świadomość malującego operatywnego ciała. Już sama enkaustyka jest niezwykle pracochłonna i niewielu artystów po nią sięga. W niepowtarzalnej strategii Gliszczyńskiego wymaga ona jeszcze więcej czasu i cierpliwości niż w jej klasycznych odsłonach. Malarz długo celebruje bowiem powstawanie każdego z obrazów, podgrzewa wosk, wdycha jego zapach, miesza z farbą, nakłada plastyczną materię grubo i obficie na powierzchnie poszczególnych obrazów, zasłaniając je, by potem w procesie drążenia ponownie odsłaniać piętrzące się warstwy. To bliski medytacji proces kiełznania emocji i zaprzęgania ich do ścisłej współpracy w kreowaniu pożądanych form. To głębokie wglądy w naturę malarstwa – jak wskazują tytuły obrazów „Diagnostyczne cięcie” z roku 2018 czy o rok późniejszego „Obrazu diagnostycznego” chodzi o diagnozę stanu medium.

Kompozycje przypominają wyściółkę narządów wewnętrznych, plastry miodu, organiczne tkanki, miąższ owoców – to biologiczna, ucieleśniona w obrazach esencja świata. Dlatego prace Gliszczyńskiego wchodzą nam pod skórę, dotykają nas na cielesnym poziomie, ponieważ ich powierzchnie są ranliwe jak skóra, spiętrzone i wydrążone; niezależnie, czy aksamitne, czy enkaustycznie lepkie – jednakowo fascynujące dla naszej cielesnej świadomości, ponieważ materia zapisała w sobie pamięć każdego gestu artysty, nakładającego i zdejmującego farbę.

Nawiązując ponownie do teorii ulubionego przez Gliszczyńskiego filozofa Merleau-Ponty’ego, można zatem stwierdzić, że malujące ciało artysty przekazuje nam swoje widzenie tkanki świata, w której tkwi. Tkanka ta ma w sobie biologiczność i organiczność, która poprzez inkrustowanie jej w ciele malarza, jest nie tylko spójna ze światem, lecz zdaje się mieć zdolność przekładania jego istoty na tkankę malarstwa. Owa tkanka jest rozpoznawalna na pierwszy rzut oka i stanowi synonim stylu Gliszczyńskiego, którego nie da się pomylić z żadnym innym.

Marta Smolińska

The Fabric of Painting

The work of Krzysztof Gliszczyński is completely steeped in painting. With conviction, inquisitiveness, and passion, he delves into ever deeper regions of the medium, exploring the materiality of the paint applied to the surface, and constantly asking questions about its role and potential as a non-human actor with an active part in the process of creation.

Gliszczyński began at an early stage to add ground marble dust to his paint. This produces the impression of an immensely velvety texture that seduces the touch. One superb example of this effect is Grey Object with Urn No. 20 and 21 from 2000, in which he deposited the “excess” elements of matter scraped from the surface of the work in its centre, like relics. Nigredo, dated a year later, likewise emanates a matt, velour-like quality from its surface, and the surface layer of black yields to the intense blue of the linear elements of the work inscribed into the substance of the paint. The earliest of the paintings on show in the exhibition at SZOKART, Palimpsest, from 1998, is oil, marble dust, and encaustic on canvas, a combination of techniques that produces an effect of velvety layers as suggested by the title—a palimpsest is a manuscript recorded on a piece of material previously used for writing, from which the original text has been removed.

The other paintings, among them works from the series Pneuma, Perpetuum pictura, and Toledo, use the encaustic technique, likewise a very haptic medium because it employs wax as the binder, titillating the “eye on the fingertip”. He thus seems to suggest that seeing is touching with the sense of sight. Our sense of touch is also aroused by pieces including two tondi, Disappearing Spot (2008) and Unobvious (2009), which are dazzlingly colourful and give the illusion of spinning.

Gliszczyński’s painting, then, is haptic in its fabric, not only appealing to our sense of sight, but also assailing our sense of touch and physical perception. His favourite philosopher and theoretician of painting is the French phenomenologist Maurice Merleau-Ponty, whose works Gliszczyński has been reading for years with an unceasing fascination and focus, so to translate their theses into an original painterly language of his own. This is clearly visible in a 2023 painting entitled Painting Lesson after Merleau-Ponty. Merleau-Ponty wrote: “Visible and mobile, my body is a thing among things; it is caught in the fabric of the world, and its cohesion is that of a thing. But because it moves itself and sees, it holds things in a circle around itself. Things are an annex or prolongation of itself; they are incrusted into its flesh, they are part of its full definition; the world is made of the same stuff as the body.” Gliszczyński’s works are incrusted in his physicality and, like his painting body, caught up in the fabric of the world with which they cohere. To extend the paraphrase of Merleau-Ponty’s words, I would add that the outward spreading movement of the artist’s body in the process of creation is a natural consequence, a maturation of seeing that leads in the final effect to a rhythmical recording of gestures on canvas and paper.

In my opinion, these gestures are recorded in the form of the fabric of the world referred to by Merleau-Ponty. Gliszczyński has translated this – so aptly – into the fabric of his painting, which comes to the fore particularly in his most recent works, now on show for the first time in the SZOKART Gallery in Poznań. Embodied in these pieces is a fibrousness, a sponginess, a moisture, a kind of stickiness. In Study for Melancholy from 2022, the reddish colours and the contrast between the smooth surface and the furrowed areas lend the work an exceptional intensity.

The meticulous, time-consuming process of applying successive layers of the “greasy” encaustic made with melted wax produces highly condensed, concentrated, tactile compositions. Their surfaces are furrowed, and each furrow reveals every layer of colour previously applied, like stratification in geology. In Concealed History (2024) there is a band of paint left unfurrowed at the bottom—is this where the titular history is concealed? Or perhaps it is played out more in the tension between the furrows and this matter at the bottom that has not laid bare the layers beneath it? The gouges are of differing depths, uncovering variously whites, yellows, or blues, which gleam in contrast to the dominant red. They lend the picture dynamism and intrigue the eyes on our fingertips, which we want to reach out to touch each of the recesses. All the paintings made in this technique are structures throbbing with subcutaneous life. They have the simplicity of single-cell organisms and the power of a colony of analogously constructed creatures that emanate energy through their strategy of multiplying. Their individual character depends largely on the tactic adopted by Gliszczyński to scoop out the excess painting material.

Thus their forms are the result of the close cooperation between the painter’s operative body, the tool he uses, and how that interacts with the surface. The artist scrupulously dibbles blobs of paint onto the pictures and gouges them off again, but does not discard them: he collects them, deposits them in plexiglass containers like relics in an urn, and then presents them as part of selected compositions, as in Delamination from the series Pneuma made in 2023, or Perpetuum pictura 3 of 2020. In this way he demonstrates to those who view his works that the painting matter circulates in the creative process, succumbing to the various formation methods implemented by the operative body of the creator. And over time, this body gains and develops something akin to a style of its own, and a muscle memory that enables it to act independently and automatically. “‘Muscle memory’ is a term commonly used in everyday discourse for the sort of embodied implicit memory that unconsciously helps us perform various motor tasks we have somehow learned through habituation, either through explicit, intentional training or simply as the result of informal, unintentional, or even unconscious learning from repeated prior experience.” As we look at these paintings, in our imagination we “scoop them out” with our own bodies, our own hands; for the echoes of our own muscle memory awaken and engage virtually in the creation of this painting fabric. We physicalize them in ourselves, allowing our gaze to move gently over every successive contour, and tensing the muscles that would be working in actually making them. They are shapes that give the impression of being self-projecting, of following the precise, repetitive movements of Gliszczyński’s operative body, which works the painting tools in such a way that seeing and movement combine. In effect, structures emerge that are to some extent self-creating in cooperation with the thinking hand; they take the initiative and perpetuate the self-creation process. They are the traces of his body, and, having accrued a somatic and visual wisdom of their own, they spread greedily and take over increasing space to be able to protrude. Gliszczyński’s method of working activates a phenomenon that I would call auto-creation, or “budding” of form, which involves responding to tropes that emerge in the creation process. Thus the materialization of an idea is not only the result of the initiative taken by the hand holding the painting tool – or, subsequently, the scraper that removes the excess paint and rhythmically makes the furrows – but is also contingent upon the activity of the form itself, a dynamic that the artist instinctively and unhesitatingly incorporates into the intertwining of seeing and movement.

It takes a lot of work to achieve results and states like these: the artist must “get their teeth into” both the fabric of the world and the fabric of the painting: both deliberately and intuitively, activating their awareness of the operative painting body. Encaustic alone is extremely labour-intensive, and few artists choose to use it. In Gliszczyński’s unique strategy, it requires even more time and patience than in its standard use. He spends a long time celebrating the creation of each of his paintings: he heats the wax, inhales its smell, mixes it with the paint, applies the pliable material thickly and generously to the surface of each one, covering the layers previously created, only to lay them bare again afterwards in the furrowing or gouging process. This is a way of working that is akin to meditation, a way of harnessing emotions to engage them in the creation of the desired forms. It offers deep insights into the nature of painting; as the titles Diagnostic Incision (2018) and Diagnostic Image (2019) suggest, it is a diagnosis of the state of the medium.

These compositions are reminiscent of the linings of internal organs, of honeycomb, of organic fibres, of fruit flesh – they are the biological essence of the world embodied as paintings. This is why Gliszczyński’s works get under our skin, touch us at the physical level – their surfaces are as vulnerable to damage as skin, ridged and furrowed; regardless of whether they are velvety or encaustically sticky, they are equally fascinating to our physical consciousness, because the matter retains, recorded in it, the memory of each one of the artist’s movements as he applied and removed the paint.

To reference once again the theories of Gliszczyński’s favourite philosopher, Merleau-Ponty, it would thus be possible to suggest that the body of the artist painting passes on to us its seeing of the fabric of the world in which it is anchored. This fabric has a biological and organic quality that, through its incrustation in the painter’s body, is not only cohesive with the world, but also seems capable of conveying its essence in the fabric of painting. This fabric is recognizable at first glance and is a synonym of Gliszczyński’s style, which is unmistakable for any other.

Marta Smolińska

Tkanka malarstwa

Twórczość Krzysztofa Gliszczyńskiego jest kompletnie zanurzona w malarstwie. Artysta ten z przekonaniem, dociekliwością i namiętnością zapuszcza się w coraz głębsze jego rejony, eksplorując materialność farby nakładanej na płaszczyznę i nieustannie pytając o jej rolę i potencjał jako nieludzkiego aktora, biorącego aktywny udział w procesie tworzenia.

Na wczesnym etapie Gliszczyński mieszał z farbą mielony pył marmurowy, który daje wrażenie niesamowitej aksamitności faktury, uwodząc dotyk. Świetnym przykładem jest tutaj „Obiekt szary z urną nr 20 i 21” z roku 2000, w którym „nadmiarowe”, wydrapane z płaszczyzny elementy materii artysta umieścił w centrum niczym relikwie. Również o rok późniejszy obraz „Nigredo” emanuje matową, jakby welurową powierzchnią, a spod warstwy czerni mocno uwidacznia się intensywnie niebieski rysunek wykonany w materii farby. Najwcześniejszy prezentowany na wystawie w galerii SZOKART obraz „Palimpsest” z 1994 roku to olej, pył marmurowy i enkaustyka na płótnie, a owo nietypowe połączenie technik przyczynia się do powstawania efektu aksamitności i wielowarstwowości, na którą wskazuje sam tytuł – palimpsest to wszak rękopis spisany na używanym już wcześniej materiale piśmiennym, z którego usunięto poprzedni tekst.

Pozostałe obrazy, m.in. te z cyklów „Pneuma”, „Perpetuum pictura” czy „Toledo” operują z kolei techniką enkaustyki – również bardzo haptyczną, ponieważ w jej ramach spoiwem jest wosk, który także kusi oko na koniuszku palca. Twórca zdaje się więc sugerować, że widzenie jest dotykaniem za pomocą wzroku. Nasz dotyk przywołują m.in. dwa tonda zatytułowane „Znikający punkt” (2008) czy „Nieoczywiste” (2009), których płaszczyzny mienią się intensywną kolorystyką i zdają się dynamicznie optycznie wirować.

Gliszczyński tworzy zatem haptyczną tkankę malarstwa, która apeluje nie tylko do zmysłu wzroku, lecz indaguje również nasz zmysł dotyku i cielesną percepcję. Ulubionym filozofem i teoretykiem malarstwa artysty jest francuski fenomenolog Maurice Merleau-Ponty, którego Gliszczyński czytuje od lat, z nieustającą fascynacją i skupieniem, by jego tezy przekładać na swój własny, oryginalny malarski język, co doskonale widać w obrazie z roku 2023 zatytułowanym „Lekcja malarstwa według Merleau-Ponty’ego”. Merleau-Ponty pisał: „Widzialne i ruchome, ciało moje zalicza się do rzeczy, jest jedną z nich; tkwi w tkance świata i jego spójność jest spójnością rzeczy. Jednakowoż, skoro widzi oraz się porusza, w krąg ustawia rzeczy wokół siebie, one zaś są jakąś jego dobudówką bądź też przedłużeniem, są inkrustowane w jego cielesności, stanowią część jego pełnej definicji i tworzywem świata jest tworzywo ciała.” Prace Gliszczyńskiego są inkrustowane w jego cielesności i podobnie jak jego malujące ciało tkwią w tkance świata, z którą są spójne. Parafrazując dalej słowa Merleau-Ponty’ego dodałabym, że rozprzestrzeniający się ruch ciała artysty w trakcie procesu tworzenia jest naturalnym następstwem, dojrzewaniem widzenia, prowadzącym w efekcie finalnym do rytmicznego zapisywania gestów na płótnach i papierach.

Moim zdaniem owe gesty zapisują się w formie owej tkanki świata, o której wspominał Merleau-Ponty. Gliszczyński przetłumaczył ją – jakże celnie – na tkankę malarstwa, która dochodzi do głosu szczególnie w ostatnich obrazach, które mają swoją premierę na wystawie w galerii SZOKART w Poznaniu. Jest w tych dziełach ucieleśniona tkankowość, gąbczastość, wilgotność, czy jakby lepkość. W „Studium do melancholii” z roku 2022 kontrast powierzchni gładkiej z tą wyżłobioną oraz czerwonawa kolorystyka nadają temu dziełu wyjątkowej intensywności.

W wyniku żmudnego i precyzyjnego nanoszenia kolejnych warstw „tłustej” enkaustyki, powstającej na bazie podgrzanego wosku, wyłaniają się kompozycje mocno skondensowane i zagęszczone, dotykalne. Ich powierzchnie są żłobione, a w każdym wgłębieniu ujawnia się i odsłania – jak stratygrafia w ramach geologii – każda kolejna warstwa nałożonej wcześniej farby. W „Ukrytej historii” z roku 2024 na dole pozostał pas farby, w której artysta nie żłobił – czy to właśnie pod nią ukrywa się tytułowa historia? A może rozgrywa się ona bardziej w napięciu między żłobieniami a materią na dole, która nie odkryła swoich spodnich warstw? Wybrania farby sięgają głębiej lub płyciej: do bieli, żółci, niebieskości, które pobłyskują na tle dominującej czerwieni, nadając obrazowi dynamiki i intrygując nasze oczy na koniuszkach palców, którymi chcielibyśmy każdego z tych wgłębień dotknąć. Wszystkie obrazy w tej technice to struktury tętniące podskórnym życiem, które mają w sobie prostotę jednokomórkowców i siłę kolonii analogicznie zbudowanych organizmów, emanujących energią dzięki strategii ich multiplikowania. Ich istota w dużym stopniu zależy od taktyki, jaką Gliszczyński przyjął, by wybierać nadmiarową materię malarską.

Formy rodzą się zatem dzięki ścisłej współpracy operatywnego ciała malarza, używanego narzędzia oraz jego styku z płaszczyzną. Artysta skrupulatnie dłubie i wydłubuje cząsteczki farby, lecz się z nimi nie rozstaje: zbiera je, umieszcza w pleksi, niczym relikty w urnie, i prezentuje jako część wybranych kompozycji jak np. w „Rozwarstwieniu” z cyklu „Pneuma” z roku 2023 czy „Perpetuum pictura 3” z roku 2020. Uzmysławia tym samym odbiorczyniom i odbiorcom swoich dzieł, że materia malarska krąży w procesie tworzenia, poddając się kształtowaniu na różne sposoby przez operatywne ciało twórcy. A owo ciało z czasem zyskuje i rozwija coś w rodzaju własnego stylu i pamięci mięśniowej, dzięki której może działać samodzielnie i automatycznie. „Pamięć mięśniowa to termin powszechnie używany w codziennym dyskursie na określenie swoistego rodzaju nieświadomej, ucieleśnionej pamięci, umożliwiającej nam, w nieuzmysłowiony sposób, wykonywanie pewnych czynności ruchowych, które opanowaliśmy wskutek przyzwyczajenia lub celowego ćwiczenia albo, po prostu, w wyniku nieformalnego, nieintencjonalnego lub wręcz nieświadomego uczenia się z wcześniejszych doświadczeń.” Patrząc na te obrazy, w wyobraźni „drążymy” je własnym ciałem i własną dłonią; odzywają się bowiem echa naszej własnej mięśniowej pamięci, która wirtualnie angażuje się w kreowanie tkanki malarstwa. Ucieleśniamy je w nas samych, przesuwając miękko wzrokiem po każdej kolejnej formie i napinając mięśnie, które pracowały(by) przy ich rzeczywistym kreowaniu. To formy, które sprawiają wrażenie samoprojektujących się, podążających za powtarzalnymi, precyzyjnymi gestami operatywnego ciała Gliszczyńskiego, który prowadzi narzędzia malarskie w taki sposób, by widzenie i ruch splotły się w jedno. W efekcie powstają struktury, które poniekąd same się kreują we współpracy z myślącą dłonią, przejmując inicjatywę i prowadząc dalej w procesie samokreacji. To ślady ciała, które – zyskując własną somatyczną i wizualną mądrość – rozprzestrzeniają się zachłannie i pozyskują coraz większą płaszczyznę, by móc się plastycznie wyłonić. Metoda pracy Gliszczyńskiego uruchamia bowiem zjawisko, które nazwałabym samokreowaniem się formy, jej „pączkowaniem”, w ramach którego podejmowane są wątki, ujawniające się w trakcie procesu tworzenia. Materializacja idei następuje zatem nie tylko wskutek przejęcia inicjatywy przez dłoń, trzymającą narzędzia malarskie i w końcu szpachlę, która usuwa nadmiar farby i drąży rytmiczne wgłębienia, lecz również w relacji do aktywności samej formy, którą to dynamikę artysta instynktownie i bez zawahania włącza w splot widzenia i ruchu.

Na taki rezultat i stan trzeba bardzo długo pracować – „wgryzać się” zarówno w tkankę świata, jak i w tkankę malarstwa: jednocześnie świadomie, jak i intuicyjnie, aktywując świadomość malującego operatywnego ciała. Już sama enkaustyka jest niezwykle pracochłonna i niewielu artystów po nią sięga. W niepowtarzalnej strategii Gliszczyńskiego wymaga ona jeszcze więcej czasu i cierpliwości niż w jej klasycznych odsłonach. Malarz długo celebruje bowiem powstawanie każdego z obrazów, podgrzewa wosk, wdycha jego zapach, miesza z farbą, nakłada plastyczną materię grubo i obficie na powierzchnie poszczególnych obrazów, zasłaniając je, by potem w procesie drążenia ponownie odsłaniać piętrzące się warstwy. To bliski medytacji proces kiełznania emocji i zaprzęgania ich do ścisłej współpracy w kreowaniu pożądanych form. To głębokie wglądy w naturę malarstwa – jak wskazują tytuły obrazów „Diagnostyczne cięcie” z roku 2018 czy o rok późniejszego „Obrazu diagnostycznego” chodzi o diagnozę stanu medium.

Kompozycje przypominają wyściółkę narządów wewnętrznych, plastry miodu, organiczne tkanki, miąższ owoców – to biologiczna, ucieleśniona w obrazach esencja świata. Dlatego prace Gliszczyńskiego wchodzą nam pod skórę, dotykają nas na cielesnym poziomie, ponieważ ich powierzchnie są ranliwe jak skóra, spiętrzone i wydrążone; niezależnie, czy aksamitne, czy enkaustycznie lepkie – jednakowo fascynujące dla naszej cielesnej świadomości, ponieważ materia zapisała w sobie pamięć każdego gestu artysty, nakładającego i zdejmującego farbę.

Nawiązując ponownie do teorii ulubionego przez Gliszczyńskiego filozofa Merleau-Ponty’ego, można zatem stwierdzić, że malujące ciało artysty przekazuje nam swoje widzenie tkanki świata, w której tkwi. Tkanka ta ma w sobie biologiczność i organiczność, która poprzez inkrustowanie jej w ciele malarza, jest nie tylko spójna ze światem, lecz zdaje się mieć zdolność przekładania jego istoty na tkankę malarstwa. Owa tkanka jest rozpoznawalna na pierwszy rzut oka i stanowi synonim stylu Gliszczyńskiego, którego nie da się pomylić z żadnym innym.

Marta Smolińska

ENG.

The Fabric of Painting

The work of Krzysztof Gliszczyński is completely steeped in painting. With conviction, inquisitiveness, and passion, he delves into ever deeper regions of the medium, exploring the materiality of the paint applied to the surface, and constantly asking questions about its role and potential as a non-human actor with an active part in the process of creation.

Gliszczyński began at an early stage to add ground marble dust to his paint. This produces the impression of an immensely velvety texture that seduces the touch. One superb example of this effect is Grey Object with Urn No. 20 and 21 from 2000, in which he deposited the “excess” elements of matter scraped from the surface of the work in its centre, like relics. Nigredo, dated a year later, likewise emanates a matt, velour-like quality from its surface, and the surface layer of black yields to the intense blue of the linear elements of the work inscribed into the substance of the paint. The earliest of the paintings on show in the exhibition at SZOKART, Palimpsest, from 1998, is oil, marble dust, and encaustic on canvas, a combination of techniques that produces an effect of velvety layers as suggested by the title—a palimpsest is a manuscript recorded on a piece of material previously used for writing, from which the original text has been removed.

The other paintings, among them works from the series Pneuma, Perpetuum pictura, and Toledo, use the encaustic technique, likewise a very haptic medium because it employs wax as the binder, titillating the “eye on the fingertip”. He thus seems to suggest that seeing is touching with the sense of sight. Our sense of touch is also aroused by pieces including two tondi, Disappearing Spot (2008) and Unobvious (2009), which are dazzlingly colourful and give the illusion of spinning.

Gliszczyński’s painting, then, is haptic in its fabric, not only appealing to our sense of sight, but also assailing our sense of touch and physical perception. His favourite philosopher and theoretician of painting is the French phenomenologist Maurice Merleau-Ponty, whose works Gliszczyński has been reading for years with an unceasing fascination and focus, so to translate their theses into an original painterly language of his own. This is clearly visible in a 2023 painting entitled Painting Lesson after Merleau-Ponty. Merleau-Ponty wrote: “Visible and mobile, my body is a thing among things; it is caught in the fabric of the world, and its cohesion is that of a thing. But because it moves itself and sees, it holds things in a circle around itself. Things are an annex or prolongation of itself; they are incrusted into its flesh, they are part of its full definition; the world is made of the same stuff as the body.” Gliszczyński’s works are incrusted in his physicality and, like his painting body, caught up in the fabric of the world with which they cohere. To extend the paraphrase of Merleau-Ponty’s words, I would add that the outward spreading movement of the artist’s body in the process of creation is a natural consequence, a maturation of seeing that leads in the final effect to a rhythmical recording of gestures on canvas and paper.

In my opinion, these gestures are recorded in the form of the fabric of the world referred to by Merleau-Ponty. Gliszczyński has translated this – so aptly – into the fabric of his painting, which comes to the fore particularly in his most recent works, now on show for the first time in the SZOKART Gallery in Poznań. Embodied in these pieces is a fibrousness, a sponginess, a moisture, a kind of stickiness. In Study for Melancholy from 2022, the reddish colours and the contrast between the smooth surface and the furrowed areas lend the work an exceptional intensity.

The meticulous, time-consuming process of applying successive layers of the “greasy” encaustic made with melted wax produces highly condensed, concentrated, tactile compositions. Their surfaces are furrowed, and each furrow reveals every layer of colour previously applied, like stratification in geology. In Concealed History (2024) there is a band of paint left unfurrowed at the bottom—is this where the titular history is concealed? Or perhaps it is played out more in the tension between the furrows and this matter at the bottom that has not laid bare the layers beneath it? The gouges are of differing depths, uncovering variously whites, yellows, or blues, which gleam in contrast to the dominant red. They lend the picture dynamism and intrigue the eyes on our fingertips, which we want to reach out to touch each of the recesses. All the paintings made in this technique are structures throbbing with subcutaneous life. They have the simplicity of single-cell organisms and the power of a colony of analogously constructed creatures that emanate energy through their strategy of multiplying. Their individual character depends largely on the tactic adopted by Gliszczyński to scoop out the excess painting material.

Thus their forms are the result of the close cooperation between the painter’s operative body, the tool he uses, and how that interacts with the surface. The artist scrupulously dibbles blobs of paint onto the pictures and gouges them off again, but does not discard them: he collects them, deposits them in plexiglass containers like relics in an urn, and then presents them as part of selected compositions, as in Delamination from the series Pneuma made in 2023, or Perpetuum pictura 3 of 2020. In this way he demonstrates to those who view his works that the painting matter circulates in the creative process, succumbing to the various formation methods implemented by the operative body of the creator. And over time, this body gains and develops something akin to a style of its own, and a muscle memory that enables it to act independently and automatically. “‘Muscle memory’ is a term commonly used in everyday discourse for the sort of embodied implicit memory that unconsciously helps us perform various motor tasks we have somehow learned through habituation, either through explicit, intentional training or simply as the result of informal, unintentional, or even unconscious learning from repeated prior experience.” As we look at these paintings, in our imagination we “scoop them out” with our own bodies, our own hands; for the echoes of our own muscle memory awaken and engage virtually in the creation of this painting fabric. We physicalize them in ourselves, allowing our gaze to move gently over every successive contour, and tensing the muscles that would be working in actually making them. They are shapes that give the impression of being self-projecting, of following the precise, repetitive movements of Gliszczyński’s operative body, which works the painting tools in such a way that seeing and movement combine. In effect, structures emerge that are to some extent self-creating in cooperation with the thinking hand; they take the initiative and perpetuate the self-creation process. They are the traces of his body, and, having accrued a somatic and visual wisdom of their own, they spread greedily and take over increasing space to be able to protrude. Gliszczyński’s method of working activates a phenomenon that I would call auto-creation, or “budding” of form, which involves responding to tropes that emerge in the creation process. Thus the materialization of an idea is not only the result of the initiative taken by the hand holding the painting tool – or, subsequently, the scraper that removes the excess paint and rhythmically makes the furrows – but is also contingent upon the activity of the form itself, a dynamic that the artist instinctively and unhesitatingly incorporates into the intertwining of seeing and movement.

It takes a lot of work to achieve results and states like these: the artist must “get their teeth into” both the fabric of the world and the fabric of the painting: both deliberately and intuitively, activating their awareness of the operative painting body. Encaustic alone is extremely labour-intensive, and few artists choose to use it. In Gliszczyński’s unique strategy, it requires even more time and patience than in its standard use. He spends a long time celebrating the creation of each of his paintings: he heats the wax, inhales its smell, mixes it with the paint, applies the pliable material thickly and generously to the surface of each one, covering the layers previously created, only to lay them bare again afterwards in the furrowing or gouging process. This is a way of working that is akin to meditation, a way of harnessing emotions to engage them in the creation of the desired forms. It offers deep insights into the nature of painting; as the titles Diagnostic Incision (2018) and Diagnostic Image (2019) suggest, it is a diagnosis of the state of the medium.

These compositions are reminiscent of the linings of internal organs, of honeycomb, of organic fibres, of fruit flesh – they are the biological essence of the world embodied as paintings. This is why Gliszczyński’s works get under our skin, touch us at the physical level – their surfaces are as vulnerable to damage as skin, ridged and furrowed; regardless of whether they are velvety or encaustically sticky, they are equally fascinating to our physical consciousness, because the matter retains, recorded in it, the memory of each one of the artist’s movements as he applied and removed the paint.

To reference once again the theories of Gliszczyński’s favourite philosopher, Merleau-Ponty, it would thus be possible to suggest that the body of the artist painting passes on to us its seeing of the fabric of the world in which it is anchored. This fabric has a biological and organic quality that, through its incrustation in the painter’s body, is not only cohesive with the world, but also seems capable of conveying its essence in the fabric of painting. This fabric is recognizable at first glance and is a synonym of Gliszczyński’s style, which is unmistakable for any other.

Marta Smolińska