Please wait while flipbook is loading. For more related info, FAQs and issues please refer to DearFlip WordPress Flipbook Plugin Help documentation.

Tomasz Ciecierski i Przemysław Matecki:

(nie)znośna lekkość malarstwa

Co wspólnego mają lama z Van Goghiem, durszlak z czerwonymi i czarnymi futerkowymi kajdankami z seks shopu czy pastelowo różowy aparat telefoniczny z rakietą do badmintona? Albo schematyczne ludziki, biegnące zawsze w lewo, z polskimi flagami, które tasują się dziko niczym karty, które wypadły z ręki nieporadnego gracza? Co łączy deski, często połamane i jakby niedbale pokryte farbą, z tzw. malarstwem sztalugowym o wielowiekowej tradycji? Jak działa zestawienie soczystej, taktylnej materii farby, płaskich fotografii i trójwymiarowych obiektów?

Otóż te pozornie niepasujące do siebie elementy z finezją i bezkompromisowo spaja wspólna twórczość Tomasza Ciecierskiego (1945-2024) i Przemysława Mateckiego (ur. 1976), która rozpoczęła się w roku 2010 i trwała do śmierci starszego z malarzy w roku 2024. Przez trzynaście lat obaj twórcy rozwinęli kilka cyklów, które – mimo że dość od siebie różne – zawsze operują poetyką kolażowo-montażową, bliską nierzadko myśleniu dadaistycznemu, surrealistycznemu czy konstruktywistycznemu. Na płótnach spotykają się bowiem idee podsuwane sobie wzajemnie przez dwóch rasowych, pełnokrwistych malarzy, którzy doskonale znają historię sztuki i malarskie kanony, a jednocześnie zawsze są gotowi do podjęcia z nimi swawolnej gry, sięgającej do pytań o status i kondycję obrazu.

Patrząc na dzieła tego duetu, można odnieść wrażenie, że powstały szybko, ponieważ mają w sobie radosną lekkość i frywolną, psotną wręcz swobodę kompozycji; jakby każda decyzja podejmowana była w uniesieniu prowokowanym przez daną chwilę wspólnej kreacji. Nic jednak bardziej mylnego – proces twórczy ani nie był dynamiczny, ani też nie odbywał się w czasie spotkań obydwu malarzy. Zarówno Tomasz Ciecierski, jak i Przemysław Matecki podejmowali swoje decyzje z samotności, w zaciszu własnych pracowni, ponieważ rozpoczęty obraz „pielgrzymował” między nimi, by z każdym z nich z osobna spędzić określony, nierzadko dość długi, nawet wielomiesięczny okres czasu. Każdy z artystów działał zatem samotnie, by „rzucić wyzwanie” drugiemu i z kolei cierpliwie czekać na kolejny ruch współmalarza.

Ten rodzaj rozciągniętego w czasie, pełnego refleksji i wyważonego procesu twórczego nie zapisał się jednak w kompozycjach, które mają w sobie coś tak naturalnego i niewymuszonego, jakby wykreowały je dzieci w trakcie swobodnej zabawy. Takie efekty mogą uzyskiwać tylko malarze przez wielkie M, którzy w malarstwie i specyfice tego medium siedzą niezwykle głęboko i którzy posiedli jego tajemnice, po prostu nieustannie malując i analizując zarówno spuściznę dawnych mistrzów, jak i sztukę XX i XXI wieku.

Na wystawie twórczości duetu Tomasz Ciecierski & Przemysław Matecki „(Nie)znośna lekkość malarstwa” w galerii SZOKART – prezentującej po raz pierwszy przegląd dzieł obu artystów z prawie całego okresu ich współpracy – najwcześniejszy obraz pochodzi z lat 2016-2017. W pierwszej chwili uwagę przyciąga na nim napięcie budujące się pomiędzy reprodukcją dzieła Aliny Szapocznikow „Krużlowa (Macierzyństwo)” z 1969 roku a fotograficznym, kolorowym portretem modelki w bikini. Mikrotematem tej kompozycji stają się zatem piersi: nagie i zwielokrotnione w płaskim przedstawieniu rzeźby słynnej polskiej artystki oraz obfite i schowane w miseczkach górnej części stroju kąpielowego młodej dziewczyny, widocznej na zdjęciu, otoczonym ramą z siana pokrytego farbą. Kontrapunktem dla tego osobliwego dialogu, konfrontującego kobiece ciało przetworzone przez sztukę z ciałem realistycznie ukazanym na fotografii, są abstrakcyjne kompozycje malarskie, dokładane na główny prostokąt obrazu niczym puzzle. Niektóre z nich balansują na granicy abstrakcji i figuratywności, wywołując asocjacje z pejzażami. Z tego niesamowitego zderzenia tak różnych światów, motywów, mediów i materii, sztuki w sztuce, wyłania się swego rodzaju traktat o obrazach, ich mocy i właściwościach. W jego ramach iluzja napotyka na realne, materialne przedmioty, namalowane wchodzi w relację z fotograficznym, płaskie zaś dyskutuje z trójwymiarowym. To małe uniwersum, w którym Tomasz Ciecierski i Przemysław Matecki zarówno sobie samym, jak i nam – odbiorczyniom i odbiorcom – niestrudzenie zadają fundamentalne pytanie: Czym jest obraz? I jakby mimochodem dopytują: Czym może być malarstwo dziś, powstające wobec fotografii i realności, która nas otacza?

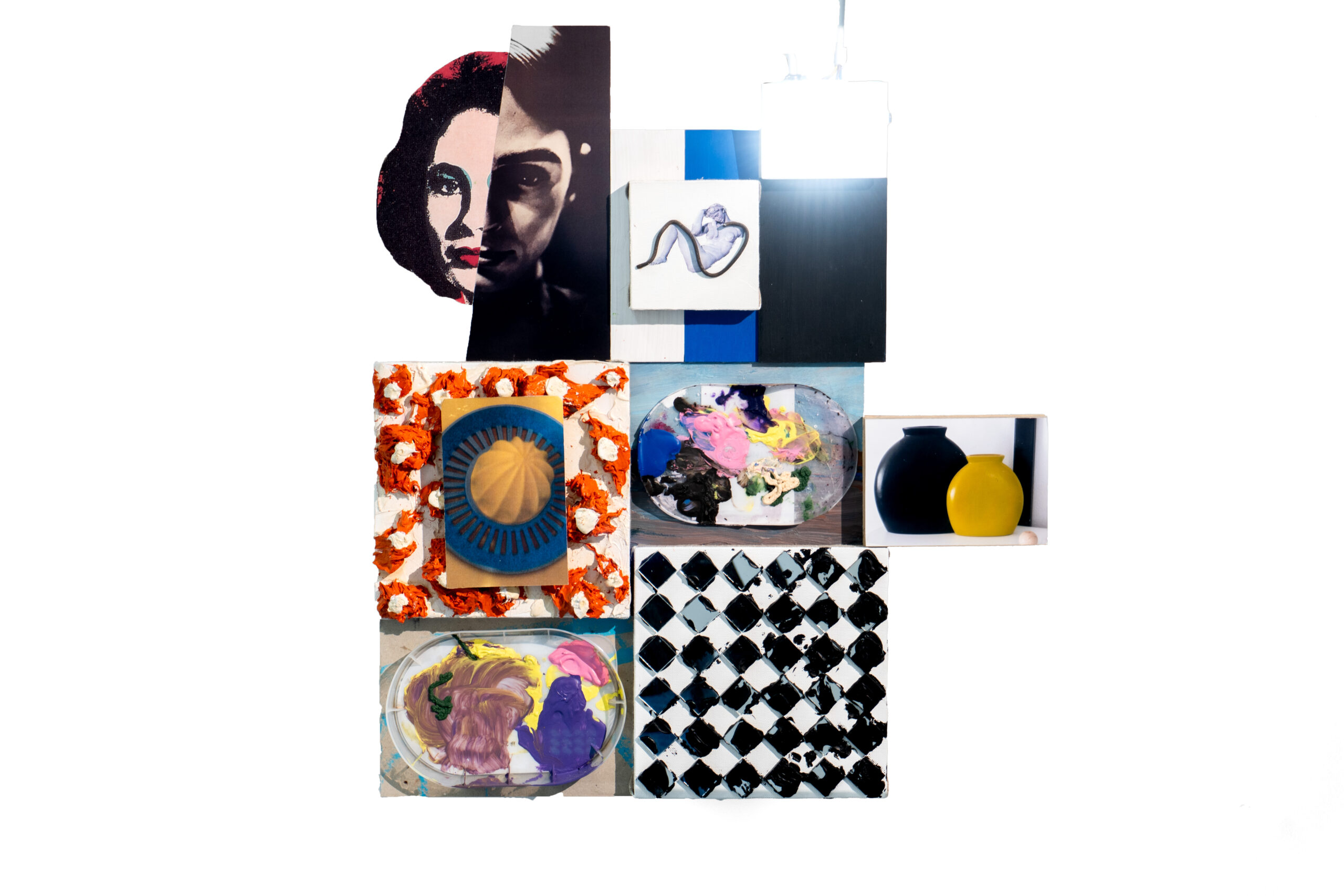

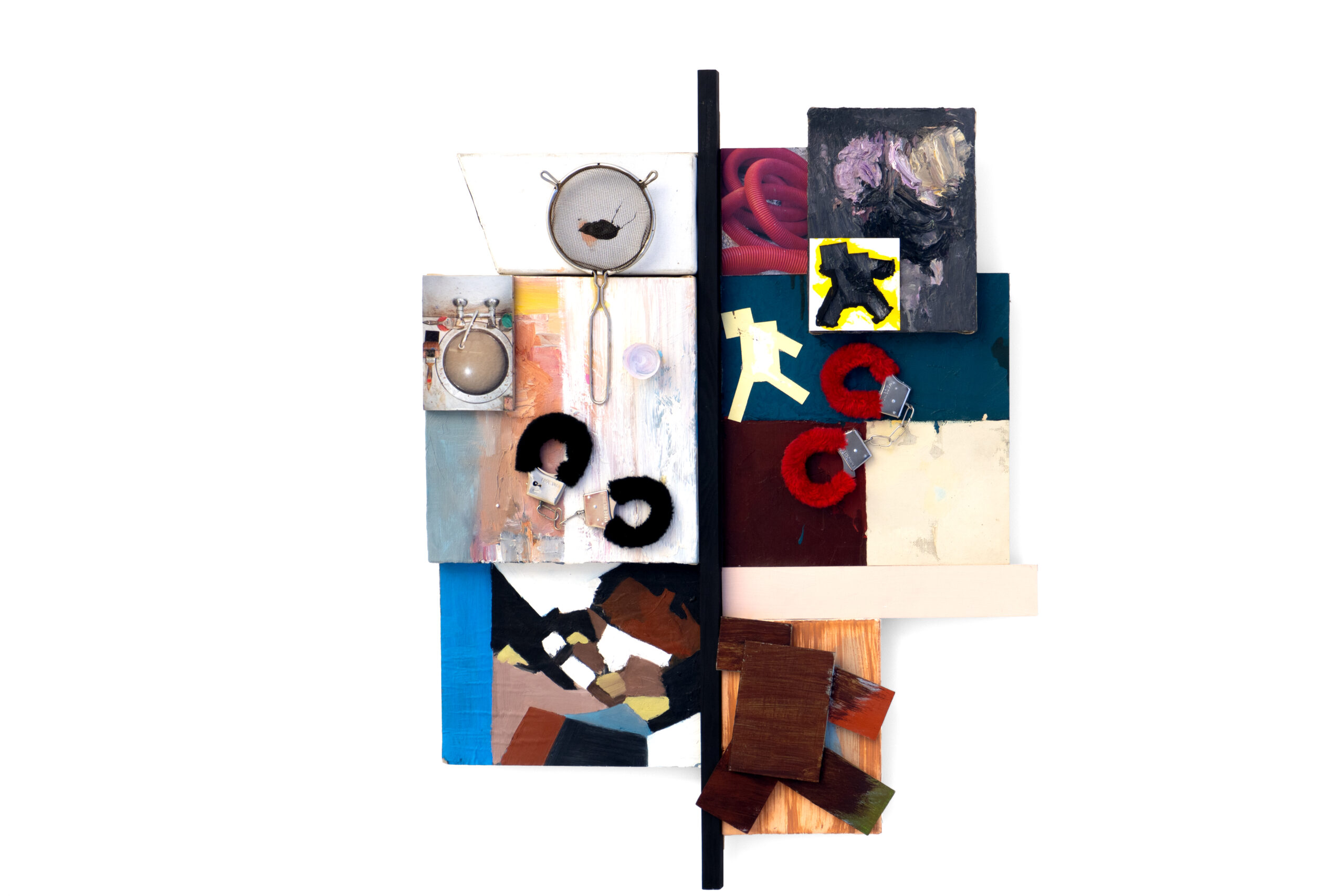

Prace z serii „Obrazy/Obiekty” z roku 2021 to jakby plansze nieznanych gier, na których nawarstwiają się obiekty, fotografie, rysunki, mniejsze płótna z impastowo nakładaną farbą. To właśnie w owej serii pojawiają się najbardziej zaskakujące zestawienia przedmiotów i motywów, a jedna z kompozycji ze zwisającym kablem sugeruje, że można ją podłączyć do prądu. Jak w combine paintings Roberta Rauschenberga z lat 50. XX wieku spotykają się w nich realne przedmioty znalezione z tym, co na wskroś malarskie i związane z gestem prowadzenia pędzla, rozprowadzającego farbę po płaszczyźnie.

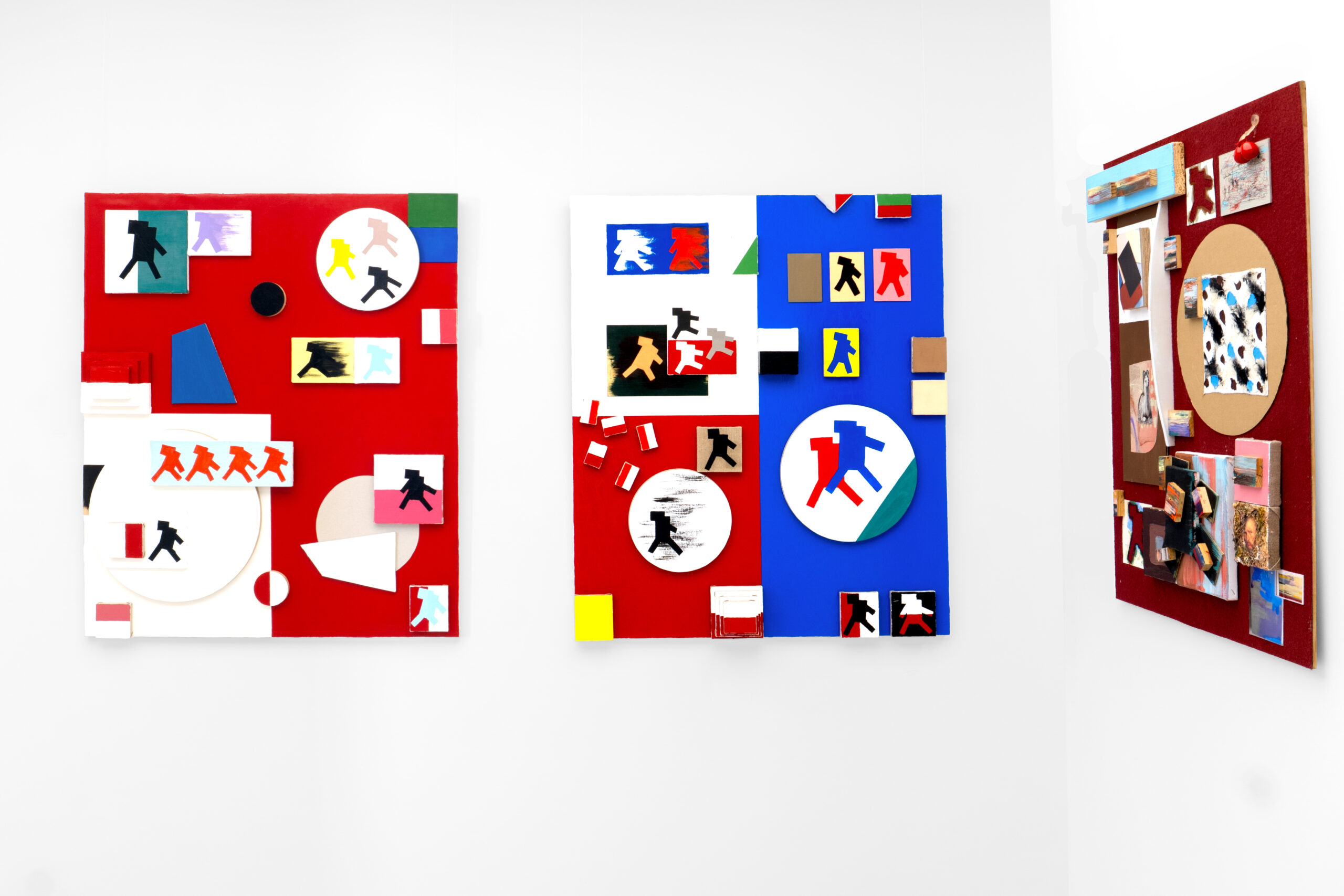

Już w „Obrazach/Obiektach” pojawiają się charakterystyczne ludziki, wykreowane przez Tomasza Ciecierskiego, które staną się znakiem rozpoznawczym cyklu „Always Look at the Left Side of Life” z 2021 roku, o którym Stach Szabłowski celnie pisał: „Artyści organizują przestrzeń każdego płótna tak jakby wykreślali mapę, jakby dzielili uniwersum obrazu, na barwne geometryczne terytoria. A może to nie mapa, tylko geometria wyrazistych podziałów właściwa dla poetyki flag i sztandarów? Białe pole, czerwone pole – wiele z prac z cyklu »Always look… «, operuje tą radykalną gamą, natrętnie kojarzącą się z polską flagą narodową. Trudno o bardziej dobitną alegorię politycznego wymiaru malarstwa; obraz jest terytorium, formy je dzielą, kolor jest emblematem tych podziałów – każdy malarski ruch to posunięcie w kształtowaniu polityki obrazu.” Stach Szabłowski trafia tu w sedno, ponieważ w twórczości Tomasza Ciecierskiego i Przemysława Mateckiego temat i treść obrazu zawsze pozostają spójne z jego formą i założeniami: to kraj(obrazy), politycznie nacechowane kompozycje, które zajmują się również polityką obrazu, jego statusem, potencjałem, ograniczeniami czy dialogami z fotografią i rzeczywistością.

Gdy każdy z tych dwóch artystów malował lub maluje osobno, zawsze każda z ich prac podejmuje pracę namysłu nad własnymi możliwościami i ograniczeniami. Z kolei, gdy tworzyli we dwóch, tendencja ta zdaje się dodatkowo wzmagać, osiągać apogeum, a każdy obraz zyskuje pogłębioną samoświadomość. Tomasz Ciecierski i Przemysław Matecki malowali bowiem po wielokrotnie ogłaszanym końcu malarstwa, z kryzysem reprezentacji w tle, kreując dzieła – zgodnie z terminologią Victora I. Stoichity – określane jako metamalarskie i samoświadome, a owa samoświadomość jest czytelna przede wszystkim w niestrudzonej autorefleksji nad przyrodzoną im kondycją i w przesuwaniu własnych granic. „Metaobrazy to obrazy, które wystawiają się na oglądanie po to, by poznać siebie; prezentują one »samowiedzę« obrazów”. Obaj artyści – przeglądając się w decyzjach tego drugiego i przyglądając się dokonanym przez niego rozstrzygnięciom – „wgryzali się” w malarstwo z zaciekłym apetytem, który nigdy nie wygasał, sugerując, że malarstwo z mitów o własnym końcu może wyciągać jedynie korzyści. I to nie zawsze z wielką powagą i patosem, lecz również z figlarnością i poczuciem humoru, które pokazują nam niezbicie, że sztuka to nie tylko misja, lecz również pole do celebrowania (nie)znośnej lekkości medium.

Tomasz Ciecierski i Przemysław Matecki aktywują zatem autorefleksyjną siłę malarstwa, które wciąż testuje swoje granice: Do jakiego stopnia obraz może stać się obiektem, by jednak wciąż pozostać obrazem? Na ile fotografia jest w stanie zdominować przedstawienie malarskie, a kiedy „przegrywa” w grze o uwagę z mięsistą materią farby? Czy obraz zawsze musi być prostokątny? Jaka dynamika pojawi się w kompozycji, gdy jej format stanie się nieregularny?

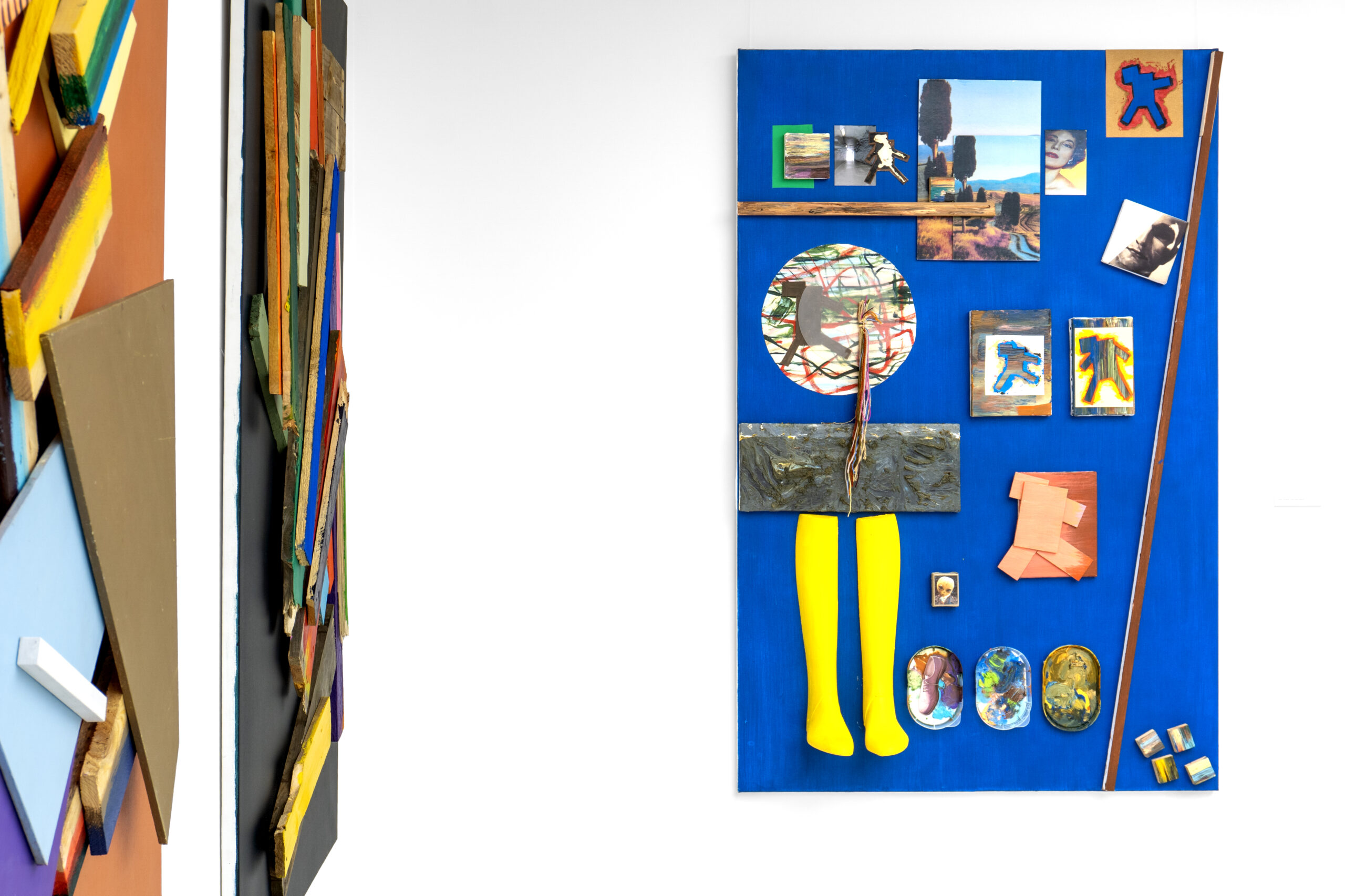

Z kolei seria prac z roku 2024 została przez Łukasza Gorczycę określona jako grę w bierki, „tyle że zagraną na odwrót – wygrywa ten, kto dołoży ostatni element nie rujnując całości.” Te kolorowe, optycznie ruchliwe kompozycje są w większości aranżowane na jednobarwnych tłach, co dodatkowo wzmaga ich wizualną dynamikę. W wypadku tej serii Tomasz Ciecierski i Przemysław Matecki rozwinęli nieco inną strategię współpracy, a mianowicie tła i deski malowali osobno, każdy w swojej pracowni, lecz – gdy później spotykali się z „półproduktami” – układy kompozycyjne tworzyli już we dwóch, by w końcu razem zmontować dany obraz.

Niektóre z tych prac powstały na drewnianych stelażach przypominających palety, spod których prześwituje ściana – czyżby artyści chcieli ujawnić ścianę jako źródłowe miejsce malarstwa? Ów efekt „paletowości” odwraca jednak uwagę od reprezentacji i iluzji, kierując skojarzenia w stronę rzeczywistości i codzienności. A może jednak jest również grą z dwuznacznością słowa „paleta”, które – szczególnie w kontekście medium malarstwa – wywołuje asocjacje przede wszystkim z płaską deską do mieszania farb, a więc nieodłącznym atrybutem malarzy? Znowu więc obraz artystycznego duetu z przymrużeniem oka kieruje nas ku malarstwu.

Ostatni wspólny obraz obu twórców to swego rodzaju dyptyk: po lewej dominuje wielki pędzel, który wyszedł spod ręki Tomasza Ciecierskiego, po prawej zaś pojawia się kompozycja jakby suprematystyczna, namalowana przez Przemysława Mateckiego. W tym momencie pracę nad kompozycją ucięło odejście starszego z malarzy na drugą stronę malarskiej tęczy, gdzie – być może – lekkość malarstwa staje się coraz bardziej znośna. We śnie Przemysław Matecki nawiązał jednak „kontakt” z kolegą z duetu, wskutek czego uzupełnił dyptyk o nowe elementy: pojawia się na nim reprodukcja „Pytii” – wyroczni z obrazu Jacka Malczewskiego, do której przychodzi ludzik, idący w prawo. Jest to zatem jedyny ludzik Tomasza Ciecierskiego, który nie podąża w lewo, a zjawia się z nietypowego kierunku, by otrzymać wróżbę. W mailowej korespondencji ze mną Przemysław Matecki napisał o procesie powstawania tego dzieła już po śmierci Tomasza Ciecierskiego: „Część ludzików to prace, które Tomek przygotowywał na tablecie. Rysował na nim palcem i zanosił do fotografa. Wywoływał to w formie zdjęć, po czym naklejał na tektury i sklejkę, tworząc w ten sposób małe obrazy. Na ostatecznej wersji naszej ostatniej pracy pojawiają się również trzy idące ludziki, namalowane na płótnie. Dalej Przemysław Matecki komentuje: „Znajdują się tam także zainstalowane pocztówki, które Tomek namiętnie zbierał i po których malował. Naklejał je również na tekturę, przygotowując do obrazu. Głównie są to włoskie pejzaże. Bywają też przygotowane na tablecie, wręcz abstrakcyjne kompozycje, wywołane potem w formie zdjęć, kompulsywne rysunki palcem na tablecie. Wspaniałe! Zainstalowane są również bardzo małe niewielkich rozmiarów wręcz kilkucentymetrowe płótna. Obrazy, które Tomek malował w latach 70., przykładając je do naszych wspólnych kompozycji mawiał ‘na świecie cię jeszcze nie było’”. Ostateczna kompozycja zawiera więc zarówno działanie wspólne obu malarzy, jak i bazuje na decyzjach Przemysława Mateckiego, który „kolażował” zarówno elementy własne, jak i te, pozostawione przez Tomasza Ciecierskiego. O ile wszystkie wcześniejsze obrazy z ludzikami miały przesłanie światopoglądowo-polityczne (zawsze idź w lewo!), o tyle ostatnia wspólna kompozycja podejmuje tematykę egzystencjalną. W mailu do mnie Przemysław Matecki napisał z kolei, że kontakt z kolegą odbywał się z raju i był przerywany: „Zrozumiałem, że te ludziki idą w stronę szczęścia. W stronę pięknego pejzażu. Zawsze chciałem, żeby ten obraz był o czymś. Będzie o dążeniu do szczęścia. Realizuje wytyczne, które zostawił Tomek. Rozmawialiśmy kilka razy o tym, żeby wrócić do tego obrazu, może używając tych materiałów, które zostały z poprzednich lat. Ale jakoś czekaliśmy na dogodny moment, który nie nadchodził. Właśnie jest. Nie ma już odwrotu.”

Marta Smolińska

Tomasz Ciecierski and Przemysław Matecki:

The (Un)Bearable Lightness of Painting

What does a llama have in common with Van Gogh, a colander with red and black fluffy handcuffs from a sex shop, and a pastel pink telephone with a badminton racquet? Or little figures, all running left, with Polish flags all jumbled together like cards fallen out of a clumsy player’s hand? What links planks of wood, often broken and as if hastily dashed with paint, with the centuries-old tradition of easel painting? How does juxtaposition of the luscious, tactile matter that is paint with flat photographs and three-dimensional objects function?

Well, these apparently unconnected elements are cohered uncompromisingly and with finesse by the joint work of Tomasz Ciecierski (1945–2024) and Przemysław Matecki (b. 1976), which began in 2010 and continued until the death of the older of the two in 2024. Over thirteen years, these two artists created several cycles which, though rather different from each other, always emanate a poetic language based on collage and assemblage that is often close to a Dadaist, surrealist, or constructivist mode of thinking. For these canvases are the landing-pads for ideas exchanged by two full-blooded, pedigree artists with an excellent knowledge of art history and the canons of painting, who are nonetheless always up for playing around with them in such a way as to provoke questions about the status and condition of the painting.

Looking at the works by this duo, one might be forgiven for having the impression that they were made hastily: they exude a joyful lightness and a frivolous, even mischievous freedom of composition, as if every decision had been taken in a euphoria evoked by that moment of shared creation. Nothing could be further from the truth, however – the creative process was neither dynamic, nor did it take place during meetings of the two artists. Both Ciecierski and Matecki took their decisions in solitude, in the quiet of their own studios, because once started, the picture “pilgrimaged” between them, spending with each of them a certain, often fairly long time, sometimes even several months. Each of them worked separately, ‘throwing down challenges’ to the other and then waiting patiently for his next move.

This extended, reflective, balanced creative process has left no trace in the compositions, however; they are as natural and unforced as if they had been made by children playing freely. Such effects can only be achieved by great painters, who have achieved intimate familiarity with the most profound secrets of painting and its unique qualities as a medium, by painting incessantly, and analysing both the legacy of the Old Masters and the art of the twentieth and twenty-first centuries.

The earliest of the paintings on display in “The (Un)Bearable Lightness of Painting” at the SZOKART Gallery – the first retrospective exhibition of works by the duo Tomasz Ciecierski & Przemysław Matecki from almost the whole period of their cooperation – dates from 2016–2017. The first thing one notices is the tension created between the reproduction of Alina Szapocznikow’s 1969 work Krużlowa (Motherhood) and the colour photograph of the model in the bikini. The micro-theme of this composition, then, is breasts: bare and intensified in this two-dimensional reproduction of the famous Polish artist’s sculpture, and voluptuous, nestled in the cups of the young girl’s bikini top on the photograph, which is framed with painted straw. The counterpoint to this curious dialogue, which confronts the female body as processed through art with a realistic photographic reproduction of the body, is supplied by the abstract painted compositions superimposed onto the main rectangle of the work like puzzle pieces. Some of them walk the balancing line between abstraction and figuration, inviting associations with landscapes. This incredible collision of such different worlds, motifs, media and materials, art within art, produces a kind of treatise on paintings, their power, and their properties. Illusion meets real, material objects, the painted relates to the photographic, and the flat discusses with the three-dimensional. This is a small universe, within which Ciecierski and Matecki tirelessly ask themselves, each other, and us, their viewers, the fundamental question: “What is a painting?” And this question is followed, as if incidentally, by a second: “What can a painting be today, created in relationship to photography and to the reality that surrounds us?”

The works in the 2021 series “Paintings/Objects” are like the boards of unfamiliar games, heaped with objects, photographs, drawings, and smaller impasto painted canvases. It is this series that comprises the most unexpected juxtapositions of objects and motifs, and one composition, with its dangling cable, almost looks like we could plug it in. As in Robert Rauschenberg’s combine paintings from the 1950s, here too, real objets trouvés meet pure painting and the action of brushwork, spreading paint across a surface.

Tomasz Ciecierski’s signature human figures also make their first appearance in “Paintings/Objects”. They go on to become the leitmotif in the cycle “Always Look at the Left Side of Life” (2021), of which Stach Szabłowski wrote perceptively: “These artists organize the space of every canvas as if they were charting a map, dividing up the universe of the painting into colourful geometric territories. Or perhaps not a map, but the geometry of the expressive divisions that characterize the poetics of flags and standards? A white field, a red field – many of the works in the cycle ‘Always Look…’ employ this radical scale that so insistently echoes the Polish national flag. It would be hard to devise a more emphatic allegory of the political dimension of painting; the painting is the territory, the shapes divide it, colour is the emblem of those divisions – every decision taken by the painter is a move in shaping the politics of the painting.” Stach Szabłowski is on point here: in the work of Ciecierski and Matecki, the theme and content of the painting are always unified with its form and premises: they are land(scape)s, politically loaded compositions that also address the politics of the painting and its status, potential, limitations, and dialogues with photography and reality.

Whenever either of these artists has painted alone, each of their works has always made the effort to ponder its own potential and limitations. When they have worked together, however, this tendency seems to intensify yet further, reaching an apogee, and each painting is imbued with a more profound self-awareness. For Ciecierski and Matecki are painting in an age when the end of painting has been proclaimed many times, an age dogged by a crisis of representation, and they create works that, according to the terminology of Victor I. Stoichita, are meta-pictures, self-aware. This self-awareness is discernible above all in their tireless self-reflection on their natural condition and in their pushing back of their own limits. “Metapictures are pictures that show themselves in order to know themselves; they stage the ‘self-knowledge’ of pictures.” Both artists, each seeing himself reflected in the decisions of the other and observing the decisions taken by the other, have “bitten into” painting with a ferocious appetite that has never abated, suggesting that painting can only benefit from the myths surrounding its own end. Moreover, they have done so not always with great seriousness and pathos, but also with mischief and a sense of humour, which show us irrefutably that art is not only a mission but also a forum for celebration of the (un)bearable lightness of the medium.

Tomasz Ciecierski and Przemysław Matecki thus activate the self-reflective power of painting that is still testing its boundaries: To what degree can a picture become an object but still remain a picture? To what extent can a photograph dominate the representation in a painting, and when does it ‘lose out’ in the game for attention with the fleshier matter of paint? Must a picture always be rectangular? What dynamic enters a composition with an irregular format?

The series of works from 2024, in turn, has been characterized by Łukasz Gorczyca as a game of spillikins, “only played in reverse – the winner is the one who adds the last element that doesn’t ruin the whole”. These colourful, optically “busy” compositions are for the most part arranged on plain backgrounds, which further intensifies their visual dynamics. In this series, Ciecierski and Matecki have developed a slightly different cooperative strategy: they painted the background and the boards separately, each in their own studio, but when they then met up with their ‘semi-finished products’, they created the compositions and assembled the pictures together.

Some of these works were made on wooden frames reminiscent of pallets, through which the walls are visible – could the artists be drawing attention to the wall as the original place for painting? This “pallet effect” in fact diverts attention from the aspects of representation and illusion, however, redirecting associations towards the real and the quotidian. Or perhaps it is also a pun with the word “palette”, which – particularly in the context of the painting medium – prompts associations above all with the flat board used to mix paints, the archetypal attribute of the painter? This is thus another picture by the artistic duo that gives a humorous nod towards painting.

The last joint picture by the pair is a kind of diptych: the left part is dominated by grand brushwork by Ciecierski, while the right is an almost suprematist-style composition painted by Matecki. At this point, work on the composition was arrested by the older of the two painters passing on across the painterly rainbow, where – perhaps – the lightness of painting becomes increasingly bearable. Matecki nonetheless made “contact” with his erstwhile partner in a dream, which enabled the latter to add new elements to the diptych: a reproduction of the oracle Pythia as painted by Jacek Malczewski, who is being visited by a little human figure facing right. This is the only of Ciecierski’s human figures not going left; it is coming from this untypical direction in order to be given a prophecy by the oracle. In an email to me, Matecki wrote about how the process of creating this work proceeded after Ciecierski’s death: “Some of the figures are works made by Tomek on a tablet. He would draw on the screen with his finger, and take the pictures to a photographer. He had them developed, and then stuck the photographs onto cardboard and plywood, so making small pictures. The final version of our last work also features three walking figures painted onto canvas.” He goes on: “There are also postcards inserted onto it. Tomek collected them with a passion and painted on them. He stuck them onto cardboard as part of his preparations for the picture. For the most part they are Italian landscapes. There are other compositions, too, abstract ones, that were worked up on the tablet and then developed as photographs, compulsive finger drawings on the tablet. Superb ones! Then there are very small canvases, just a few centimetres in size, also installed on it. Pictures Tomek painted in the ’70s he would add to our joint compositions, saying: ‘you weren’t even born’ as he put them on.” So the final composition incorporates both joint work by both painters and relies on decisions taken by Matecki, who ‘collaged in’ both elements of his own and others left behind by Ciecierski. While all the previous paintings featuring human figures had a socio-political message (always go left!), their final joint composition addresses an existential theme. In his email to me, Matecki wrote that his contact with his friend had come from paradise, and had been patchy: “I understood that the figures were walking in the direction of happiness. Towards a beautiful landscape. I always wanted that picture to be about something. It will be about striving for happiness. It fulfils the instructions that Tomek left. We talked about returning to that picture several times, perhaps using materials left over from years past. But somehow, we were waiting for a suitable moment, which never came. It’s come now. There’s no going back now.”

Marta Smolińska

Tomasz Ciecierski i Przemysław Matecki:

(nie)znośna lekkość malarstwa

Co wspólnego mają lama z Van Goghiem, durszlak z czerwonymi i czarnymi futerkowymi kajdankami z seks shopu czy pastelowo różowy aparat telefoniczny z rakietą do badmintona? Albo schematyczne ludziki, biegnące zawsze w lewo, z polskimi flagami, które tasują się dziko niczym karty, które wypadły z ręki nieporadnego gracza? Co łączy deski, często połamane i jakby niedbale pokryte farbą, z tzw. malarstwem sztalugowym o wielowiekowej tradycji? Jak działa zestawienie soczystej, taktylnej materii farby, płaskich fotografii i trójwymiarowych obiektów?

Otóż te pozornie niepasujące do siebie elementy z finezją i bezkompromisowo spaja wspólna twórczość Tomasza Ciecierskiego (1945-2024) i Przemysława Mateckiego (ur. 1976), która rozpoczęła się w roku 2010 i trwała do śmierci starszego z malarzy w roku 2024. Przez trzynaście lat obaj twórcy rozwinęli kilka cyklów, które – mimo że dość od siebie różne – zawsze operują poetyką kolażowo-montażową, bliską nierzadko myśleniu dadaistycznemu, surrealistycznemu czy konstruktywistycznemu. Na płótnach spotykają się bowiem idee podsuwane sobie wzajemnie przez dwóch rasowych, pełnokrwistych malarzy, którzy doskonale znają historię sztuki i malarskie kanony, a jednocześnie zawsze są gotowi do podjęcia z nimi swawolnej gry, sięgającej do pytań o status i kondycję obrazu.

Patrząc na dzieła tego duetu, można odnieść wrażenie, że powstały szybko, ponieważ mają w sobie radosną lekkość i frywolną, psotną wręcz swobodę kompozycji; jakby każda decyzja podejmowana była w uniesieniu prowokowanym przez daną chwilę wspólnej kreacji. Nic jednak bardziej mylnego – proces twórczy ani nie był dynamiczny, ani też nie odbywał się w czasie spotkań obydwu malarzy. Zarówno Tomasz Ciecierski, jak i Przemysław Matecki podejmowali swoje decyzje z samotności, w zaciszu własnych pracowni, ponieważ rozpoczęty obraz „pielgrzymował” między nimi, by z każdym z nich z osobna spędzić określony, nierzadko dość długi, nawet wielomiesięczny okres czasu. Każdy z artystów działał zatem samotnie, by „rzucić wyzwanie” drugiemu i z kolei cierpliwie czekać na kolejny ruch współmalarza.

Ten rodzaj rozciągniętego w czasie, pełnego refleksji i wyważonego procesu twórczego nie zapisał się jednak w kompozycjach, które mają w sobie coś tak naturalnego i niewymuszonego, jakby wykreowały je dzieci w trakcie swobodnej zabawy. Takie efekty mogą uzyskiwać tylko malarze przez wielkie M, którzy w malarstwie i specyfice tego medium siedzą niezwykle głęboko i którzy posiedli jego tajemnice, po prostu nieustannie malując i analizując zarówno spuściznę dawnych mistrzów, jak i sztukę XX i XXI wieku.

Na wystawie twórczości duetu Tomasz Ciecierski & Przemysław Matecki „(Nie)znośna lekkość malarstwa” w galerii SZOKART – prezentującej po raz pierwszy przegląd dzieł obu artystów z prawie całego okresu ich współpracy – najwcześniejszy obraz pochodzi z lat 2016-2017. W pierwszej chwili uwagę przyciąga na nim napięcie budujące się pomiędzy reprodukcją dzieła Aliny Szapocznikow „Krużlowa (Macierzyństwo)” z 1969 roku a fotograficznym, kolorowym portretem modelki w bikini. Mikrotematem tej kompozycji stają się zatem piersi: nagie i zwielokrotnione w płaskim przedstawieniu rzeźby słynnej polskiej artystki oraz obfite i schowane w miseczkach górnej części stroju kąpielowego młodej dziewczyny, widocznej na zdjęciu, otoczonym ramą z siana pokrytego farbą. Kontrapunktem dla tego osobliwego dialogu, konfrontującego kobiece ciało przetworzone przez sztukę z ciałem realistycznie ukazanym na fotografii, są abstrakcyjne kompozycje malarskie, dokładane na główny prostokąt obrazu niczym puzzle. Niektóre z nich balansują na granicy abstrakcji i figuratywności, wywołując asocjacje z pejzażami. Z tego niesamowitego zderzenia tak różnych światów, motywów, mediów i materii, sztuki w sztuce, wyłania się swego rodzaju traktat o obrazach, ich mocy i właściwościach. W jego ramach iluzja napotyka na realne, materialne przedmioty, namalowane wchodzi w relację z fotograficznym, płaskie zaś dyskutuje z trójwymiarowym. To małe uniwersum, w którym Tomasz Ciecierski i Przemysław Matecki zarówno sobie samym, jak i nam – odbiorczyniom i odbiorcom – niestrudzenie zadają fundamentalne pytanie: Czym jest obraz? I jakby mimochodem dopytują: Czym może być malarstwo dziś, powstające wobec fotografii i realności, która nas otacza?

Prace z serii „Obrazy/Obiekty” z roku 2021 to jakby plansze nieznanych gier, na których nawarstwiają się obiekty, fotografie, rysunki, mniejsze płótna z impastowo nakładaną farbą. To właśnie w owej serii pojawiają się najbardziej zaskakujące zestawienia przedmiotów i motywów, a jedna z kompozycji ze zwisającym kablem sugeruje, że można ją podłączyć do prądu. Jak w combine paintings Roberta Rauschenberga z lat 50. XX wieku spotykają się w nich realne przedmioty znalezione z tym, co na wskroś malarskie i związane z gestem prowadzenia pędzla, rozprowadzającego farbę po płaszczyźnie.

Już w „Obrazach/Obiektach” pojawiają się charakterystyczne ludziki, wykreowane przez Tomasza Ciecierskiego, które staną się znakiem rozpoznawczym cyklu „Always Look at the Left Side of Life” z 2021 roku, o którym Stach Szabłowski celnie pisał: „Artyści organizują przestrzeń każdego płótna tak jakby wykreślali mapę, jakby dzielili uniwersum obrazu, na barwne geometryczne terytoria. A może to nie mapa, tylko geometria wyrazistych podziałów właściwa dla poetyki flag i sztandarów? Białe pole, czerwone pole – wiele z prac z cyklu »Always look… «, operuje tą radykalną gamą, natrętnie kojarzącą się z polską flagą narodową. Trudno o bardziej dobitną alegorię politycznego wymiaru malarstwa; obraz jest terytorium, formy je dzielą, kolor jest emblematem tych podziałów – każdy malarski ruch to posunięcie w kształtowaniu polityki obrazu.” Stach Szabłowski trafia tu w sedno, ponieważ w twórczości Tomasza Ciecierskiego i Przemysława Mateckiego temat i treść obrazu zawsze pozostają spójne z jego formą i założeniami: to kraj(obrazy), politycznie nacechowane kompozycje, które zajmują się również polityką obrazu, jego statusem, potencjałem, ograniczeniami czy dialogami z fotografią i rzeczywistością.

Gdy każdy z tych dwóch artystów malował lub maluje osobno, zawsze każda z ich prac podejmuje pracę namysłu nad własnymi możliwościami i ograniczeniami. Z kolei, gdy tworzyli we dwóch, tendencja ta zdaje się dodatkowo wzmagać, osiągać apogeum, a każdy obraz zyskuje pogłębioną samoświadomość. Tomasz Ciecierski i Przemysław Matecki malowali bowiem po wielokrotnie ogłaszanym końcu malarstwa, z kryzysem reprezentacji w tle, kreując dzieła – zgodnie z terminologią Victora I. Stoichity – określane jako metamalarskie i samoświadome, a owa samoświadomość jest czytelna przede wszystkim w niestrudzonej autorefleksji nad przyrodzoną im kondycją i w przesuwaniu własnych granic. „Metaobrazy to obrazy, które wystawiają się na oglądanie po to, by poznać siebie; prezentują one »samowiedzę« obrazów”. Obaj artyści – przeglądając się w decyzjach tego drugiego i przyglądając się dokonanym przez niego rozstrzygnięciom – „wgryzali się” w malarstwo z zaciekłym apetytem, który nigdy nie wygasał, sugerując, że malarstwo z mitów o własnym końcu może wyciągać jedynie korzyści. I to nie zawsze z wielką powagą i patosem, lecz również z figlarnością i poczuciem humoru, które pokazują nam niezbicie, że sztuka to nie tylko misja, lecz również pole do celebrowania (nie)znośnej lekkości medium.

Tomasz Ciecierski i Przemysław Matecki aktywują zatem autorefleksyjną siłę malarstwa, które wciąż testuje swoje granice: Do jakiego stopnia obraz może stać się obiektem, by jednak wciąż pozostać obrazem? Na ile fotografia jest w stanie zdominować przedstawienie malarskie, a kiedy „przegrywa” w grze o uwagę z mięsistą materią farby? Czy obraz zawsze musi być prostokątny? Jaka dynamika pojawi się w kompozycji, gdy jej format stanie się nieregularny?

Z kolei seria prac z roku 2024 została przez Łukasza Gorczycę określona jako grę w bierki, „tyle że zagraną na odwrót – wygrywa ten, kto dołoży ostatni element nie rujnując całości.” Te kolorowe, optycznie ruchliwe kompozycje są w większości aranżowane na jednobarwnych tłach, co dodatkowo wzmaga ich wizualną dynamikę. W wypadku tej serii Tomasz Ciecierski i Przemysław Matecki rozwinęli nieco inną strategię współpracy, a mianowicie tła i deski malowali osobno, każdy w swojej pracowni, lecz – gdy później spotykali się z „półproduktami” – układy kompozycyjne tworzyli już we dwóch, by w końcu razem zmontować dany obraz.

Niektóre z tych prac powstały na drewnianych stelażach przypominających palety, spod których prześwituje ściana – czyżby artyści chcieli ujawnić ścianę jako źródłowe miejsce malarstwa? Ów efekt „paletowości” odwraca jednak uwagę od reprezentacji i iluzji, kierując skojarzenia w stronę rzeczywistości i codzienności. A może jednak jest również grą z dwuznacznością słowa „paleta”, które – szczególnie w kontekście medium malarstwa – wywołuje asocjacje przede wszystkim z płaską deską do mieszania farb, a więc nieodłącznym atrybutem malarzy? Znowu więc obraz artystycznego duetu z przymrużeniem oka kieruje nas ku malarstwu.

Ostatni wspólny obraz obu twórców to swego rodzaju dyptyk: po lewej dominuje wielki pędzel, który wyszedł spod ręki Tomasza Ciecierskiego, po prawej zaś pojawia się kompozycja jakby suprematystyczna, namalowana przez Przemysława Mateckiego. W tym momencie pracę nad kompozycją ucięło odejście starszego z malarzy na drugą stronę malarskiej tęczy, gdzie – być może – lekkość malarstwa staje się coraz bardziej znośna. We śnie Przemysław Matecki nawiązał jednak „kontakt” z kolegą z duetu, wskutek czego uzupełnił dyptyk o nowe elementy: pojawia się na nim reprodukcja „Pytii” – wyroczni z obrazu Jacka Malczewskiego, do której przychodzi ludzik, idący w prawo. Jest to zatem jedyny ludzik Tomasza Ciecierskiego, który nie podąża w lewo, a zjawia się z nietypowego kierunku, by otrzymać wróżbę. W mailowej korespondencji ze mną Przemysław Matecki napisał o procesie powstawania tego dzieła już po śmierci Tomasza Ciecierskiego: „Część ludzików to prace, które Tomek przygotowywał na tablecie. Rysował na nim palcem i zanosił do fotografa. Wywoływał to w formie zdjęć, po czym naklejał na tektury i sklejkę, tworząc w ten sposób małe obrazy. Na ostatecznej wersji naszej ostatniej pracy pojawiają się również trzy idące ludziki, namalowane na płótnie. Dalej Przemysław Matecki komentuje: „Znajdują się tam także zainstalowane pocztówki, które Tomek namiętnie zbierał i po których malował. Naklejał je również na tekturę, przygotowując do obrazu. Głównie są to włoskie pejzaże. Bywają też przygotowane na tablecie, wręcz abstrakcyjne kompozycje, wywołane potem w formie zdjęć, kompulsywne rysunki palcem na tablecie. Wspaniałe! Zainstalowane są również bardzo małe niewielkich rozmiarów wręcz kilkucentymetrowe płótna. Obrazy, które Tomek malował w latach 70., przykładając je do naszych wspólnych kompozycji mawiał ‘na świecie cię jeszcze nie było’”. Ostateczna kompozycja zawiera więc zarówno działanie wspólne obu malarzy, jak i bazuje na decyzjach Przemysława Mateckiego, który „kolażował” zarówno elementy własne, jak i te, pozostawione przez Tomasza Ciecierskiego. O ile wszystkie wcześniejsze obrazy z ludzikami miały przesłanie światopoglądowo-polityczne (zawsze idź w lewo!), o tyle ostatnia wspólna kompozycja podejmuje tematykę egzystencjalną. W mailu do mnie Przemysław Matecki napisał z kolei, że kontakt z kolegą odbywał się z raju i był przerywany: „Zrozumiałem, że te ludziki idą w stronę szczęścia. W stronę pięknego pejzażu. Zawsze chciałem, żeby ten obraz był o czymś. Będzie o dążeniu do szczęścia. Realizuje wytyczne, które zostawił Tomek. Rozmawialiśmy kilka razy o tym, żeby wrócić do tego obrazu, może używając tych materiałów, które zostały z poprzednich lat. Ale jakoś czekaliśmy na dogodny moment, który nie nadchodził. Właśnie jest. Nie ma już odwrotu.”

Marta Smolińska

ENG.

Tomasz Ciecierski and Przemysław Matecki:

The (Un)Bearable Lightness of Painting

What does a llama have in common with Van Gogh, a colander with red and black fluffy handcuffs from a sex shop, and a pastel pink telephone with a badminton racquet? Or little figures, all running left, with Polish flags all jumbled together like cards fallen out of a clumsy player’s hand? What links planks of wood, often broken and as if hastily dashed with paint, with the centuries-old tradition of easel painting? How does juxtaposition of the luscious, tactile matter that is paint with flat photographs and three-dimensional objects function?

Well, these apparently unconnected elements are cohered uncompromisingly and with finesse by the joint work of Tomasz Ciecierski (1945–2024) and Przemysław Matecki (b. 1976), which began in 2010 and continued until the death of the older of the two in 2024. Over thirteen years, these two artists created several cycles which, though rather different from each other, always emanate a poetic language based on collage and assemblage that is often close to a Dadaist, surrealist, or constructivist mode of thinking. For these canvases are the landing-pads for ideas exchanged by two full-blooded, pedigree artists with an excellent knowledge of art history and the canons of painting, who are nonetheless always up for playing around with them in such a way as to provoke questions about the status and condition of the painting.

Looking at the works by this duo, one might be forgiven for having the impression that they were made hastily: they exude a joyful lightness and a frivolous, even mischievous freedom of composition, as if every decision had been taken in a euphoria evoked by that moment of shared creation. Nothing could be further from the truth, however – the creative process was neither dynamic, nor did it take place during meetings of the two artists. Both Ciecierski and Matecki took their decisions in solitude, in the quiet of their own studios, because once started, the picture “pilgrimaged” between them, spending with each of them a certain, often fairly long time, sometimes even several months. Each of them worked separately, ‘throwing down challenges’ to the other and then waiting patiently for his next move.

This extended, reflective, balanced creative process has left no trace in the compositions, however; they are as natural and unforced as if they had been made by children playing freely. Such effects can only be achieved by great painters, who have achieved intimate familiarity with the most profound secrets of painting and its unique qualities as a medium, by painting incessantly, and analysing both the legacy of the Old Masters and the art of the twentieth and twenty-first centuries.

The earliest of the paintings on display in “The (Un)Bearable Lightness of Painting” at the SZOKART Gallery – the first retrospective exhibition of works by the duo Tomasz Ciecierski & Przemysław Matecki from almost the whole period of their cooperation – dates from 2016–2017. The first thing one notices is the tension created between the reproduction of Alina Szapocznikow’s 1969 work Krużlowa (Motherhood) and the colour photograph of the model in the bikini. The micro-theme of this composition, then, is breasts: bare and intensified in this two-dimensional reproduction of the famous Polish artist’s sculpture, and voluptuous, nestled in the cups of the young girl’s bikini top on the photograph, which is framed with painted straw. The counterpoint to this curious dialogue, which confronts the female body as processed through art with a realistic photographic reproduction of the body, is supplied by the abstract painted compositions superimposed onto the main rectangle of the work like puzzle pieces. Some of them walk the balancing line between abstraction and figuration, inviting associations with landscapes. This incredible collision of such different worlds, motifs, media and materials, art within art, produces a kind of treatise on paintings, their power, and their properties. Illusion meets real, material objects, the painted relates to the photographic, and the flat discusses with the three-dimensional. This is a small universe, within which Ciecierski and Matecki tirelessly ask themselves, each other, and us, their viewers, the fundamental question: “What is a painting?” And this question is followed, as if incidentally, by a second: “What can a painting be today, created in relationship to photography and to the reality that surrounds us?”

The works in the 2021 series “Paintings/Objects” are like the boards of unfamiliar games, heaped with objects, photographs, drawings, and smaller impasto painted canvases. It is this series that comprises the most unexpected juxtapositions of objects and motifs, and one composition, with its dangling cable, almost looks like we could plug it in. As in Robert Rauschenberg’s combine paintings from the 1950s, here too, real objets trouvés meet pure painting and the action of brushwork, spreading paint across a surface.

Tomasz Ciecierski’s signature human figures also make their first appearance in “Paintings/Objects”. They go on to become the leitmotif in the cycle “Always Look at the Left Side of Life” (2021), of which Stach Szabłowski wrote perceptively: “These artists organize the space of every canvas as if they were charting a map, dividing up the universe of the painting into colourful geometric territories. Or perhaps not a map, but the geometry of the expressive divisions that characterize the poetics of flags and standards? A white field, a red field – many of the works in the cycle ‘Always Look…’ employ this radical scale that so insistently echoes the Polish national flag. It would be hard to devise a more emphatic allegory of the political dimension of painting; the painting is the territory, the shapes divide it, colour is the emblem of those divisions – every decision taken by the painter is a move in shaping the politics of the painting.” Stach Szabłowski is on point here: in the work of Ciecierski and Matecki, the theme and content of the painting are always unified with its form and premises: they are land(scape)s, politically loaded compositions that also address the politics of the painting and its status, potential, limitations, and dialogues with photography and reality.

Whenever either of these artists has painted alone, each of their works has always made the effort to ponder its own potential and limitations. When they have worked together, however, this tendency seems to intensify yet further, reaching an apogee, and each painting is imbued with a more profound self-awareness. For Ciecierski and Matecki are painting in an age when the end of painting has been proclaimed many times, an age dogged by a crisis of representation, and they create works that, according to the terminology of Victor I. Stoichita, are meta-pictures, self-aware. This self-awareness is discernible above all in their tireless self-reflection on their natural condition and in their pushing back of their own limits. “Metapictures are pictures that show themselves in order to know themselves; they stage the ‘self-knowledge’ of pictures.” Both artists, each seeing himself reflected in the decisions of the other and observing the decisions taken by the other, have “bitten into” painting with a ferocious appetite that has never abated, suggesting that painting can only benefit from the myths surrounding its own end. Moreover, they have done so not always with great seriousness and pathos, but also with mischief and a sense of humour, which show us irrefutably that art is not only a mission but also a forum for celebration of the (un)bearable lightness of the medium.

Tomasz Ciecierski and Przemysław Matecki thus activate the self-reflective power of painting that is still testing its boundaries: To what degree can a picture become an object but still remain a picture? To what extent can a photograph dominate the representation in a painting, and when does it ‘lose out’ in the game for attention with the fleshier matter of paint? Must a picture always be rectangular? What dynamic enters a composition with an irregular format?

The series of works from 2024, in turn, has been characterized by Łukasz Gorczyca as a game of spillikins, “only played in reverse – the winner is the one who adds the last element that doesn’t ruin the whole”. These colourful, optically “busy” compositions are for the most part arranged on plain backgrounds, which further intensifies their visual dynamics. In this series, Ciecierski and Matecki have developed a slightly different cooperative strategy: they painted the background and the boards separately, each in their own studio, but when they then met up with their ‘semi-finished products’, they created the compositions and assembled the pictures together.

Some of these works were made on wooden frames reminiscent of pallets, through which the walls are visible – could the artists be drawing attention to the wall as the original place for painting? This “pallet effect” in fact diverts attention from the aspects of representation and illusion, however, redirecting associations towards the real and the quotidian. Or perhaps it is also a pun with the word “palette”, which – particularly in the context of the painting medium – prompts associations above all with the flat board used to mix paints, the archetypal attribute of the painter? This is thus another picture by the artistic duo that gives a humorous nod towards painting.

The last joint picture by the pair is a kind of diptych: the left part is dominated by grand brushwork by Ciecierski, while the right is an almost suprematist-style composition painted by Matecki. At this point, work on the composition was arrested by the older of the two painters passing on across the painterly rainbow, where – perhaps – the lightness of painting becomes increasingly bearable. Matecki nonetheless made “contact” with his erstwhile partner in a dream, which enabled the latter to add new elements to the diptych: a reproduction of the oracle Pythia as painted by Jacek Malczewski, who is being visited by a little human figure facing right. This is the only of Ciecierski’s human figures not going left; it is coming from this untypical direction in order to be given a prophecy by the oracle. In an email to me, Matecki wrote about how the process of creating this work proceeded after Ciecierski’s death: “Some of the figures are works made by Tomek on a tablet. He would draw on the screen with his finger, and take the pictures to a photographer. He had them developed, and then stuck the photographs onto cardboard and plywood, so making small pictures. The final version of our last work also features three walking figures painted onto canvas.” He goes on: “There are also postcards inserted onto it. Tomek collected them with a passion and painted on them. He stuck them onto cardboard as part of his preparations for the picture. For the most part they are Italian landscapes. There are other compositions, too, abstract ones, that were worked up on the tablet and then developed as photographs, compulsive finger drawings on the tablet. Superb ones! Then there are very small canvases, just a few centimetres in size, also installed on it. Pictures Tomek painted in the ’70s he would add to our joint compositions, saying: ‘you weren’t even born’ as he put them on.” So the final composition incorporates both joint work by both painters and relies on decisions taken by Matecki, who ‘collaged in’ both elements of his own and others left behind by Ciecierski. While all the previous paintings featuring human figures had a socio-political message (always go left!), their final joint composition addresses an existential theme. In his email to me, Matecki wrote that his contact with his friend had come from paradise, and had been patchy: “I understood that the figures were walking in the direction of happiness. Towards a beautiful landscape. I always wanted that picture to be about something. It will be about striving for happiness. It fulfils the instructions that Tomek left. We talked about returning to that picture several times, perhaps using materials left over from years past. But somehow, we were waiting for a suitable moment, which never came. It’s come now. There’s no going back now.”

Marta Smolińska