Paweł Althamer/Artur Żmijewski

Please wait while flipbook is loading. For more related info, FAQs and issues please refer to DearFlip WordPress Flipbook Plugin Help documentation.

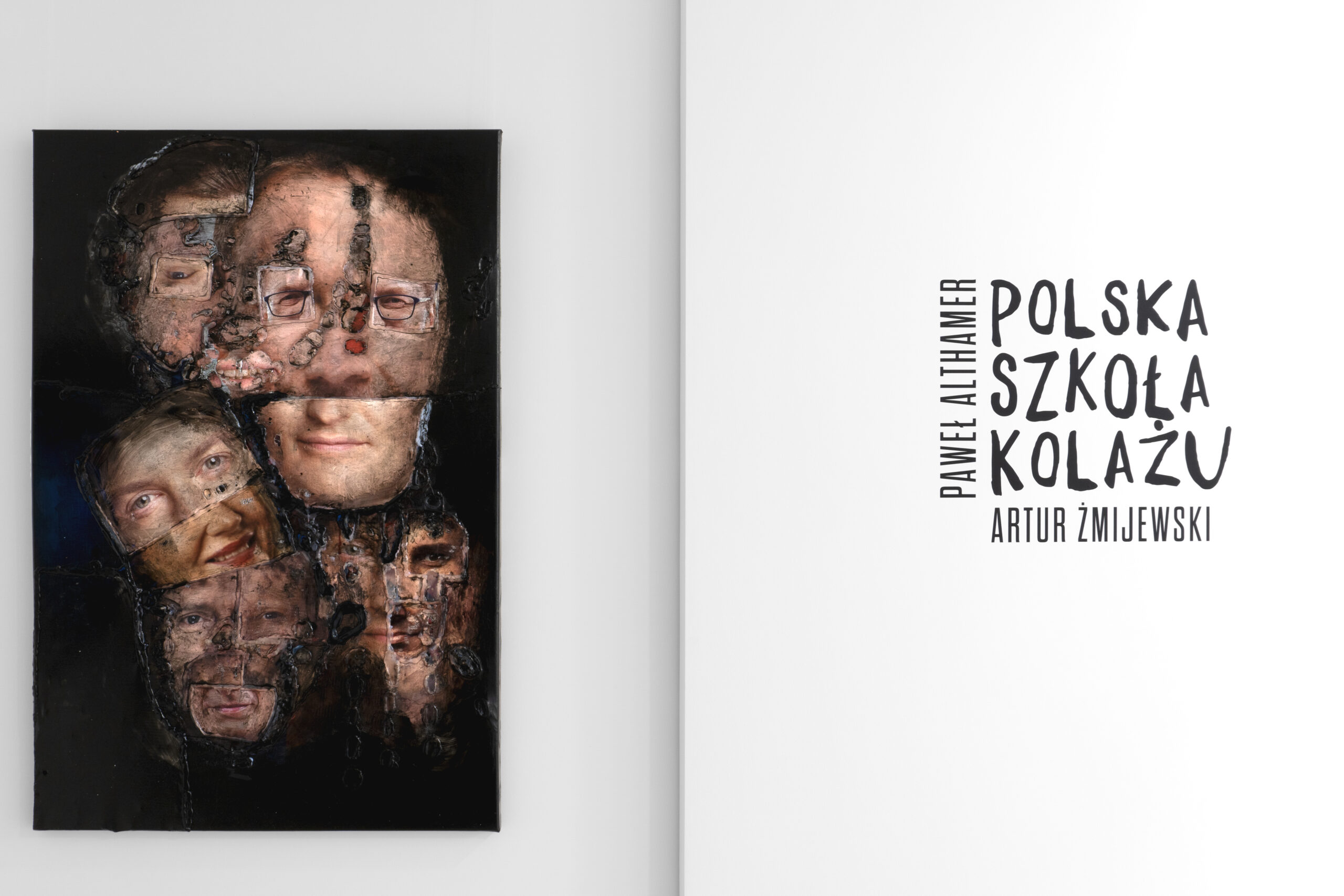

Polska szkoła kolażu:

Pawła Althamera i Artura Żmijewskiego układanie różnic

„Jak można nie widzieć, że tylko to, co najpierw zostało rozdzielone, rozcięte, będzie się sklejać z siłą? Że tylko to, co najpierw było w kontakcie, oddzieli się i ‘przetnie’ intensywnie?” – tak o wyjątkowości i potencjale techniki kolażu pisał francuski filozof i historyk sztuki Georges Didi-Huberman. Gdy patrzę na prace Pawła Althamera i Artura Żmijewskiego, wykonywane przez nich w duecie, jestem przekonana, że ci dwaj twórcy nie tylko bardzo przenikliwie dostrzegają te aspekty, lecz również potrafią uruchomić przyrodzony im charakter. Myślę również, że w tym konkretnym kontekście nie bez znaczenia pozostają słowa „siła” i „intensywność”, ponieważ obaj artyści „ścierają” i „siłują się” ze sobą, budując poszczególne kompozycje, negocjując w nich przestrzeń dla decyzji każdego z nich czy odpowiadając gestem na gest. Dzieła, powstające na papierach i płótnach, oraz wspólnie wykonane rzeźby są pełne napięcia i zapisanej w nich procesualnej energii, iskrzącej się śladami osobowości Althamera i Żmijewskiego.

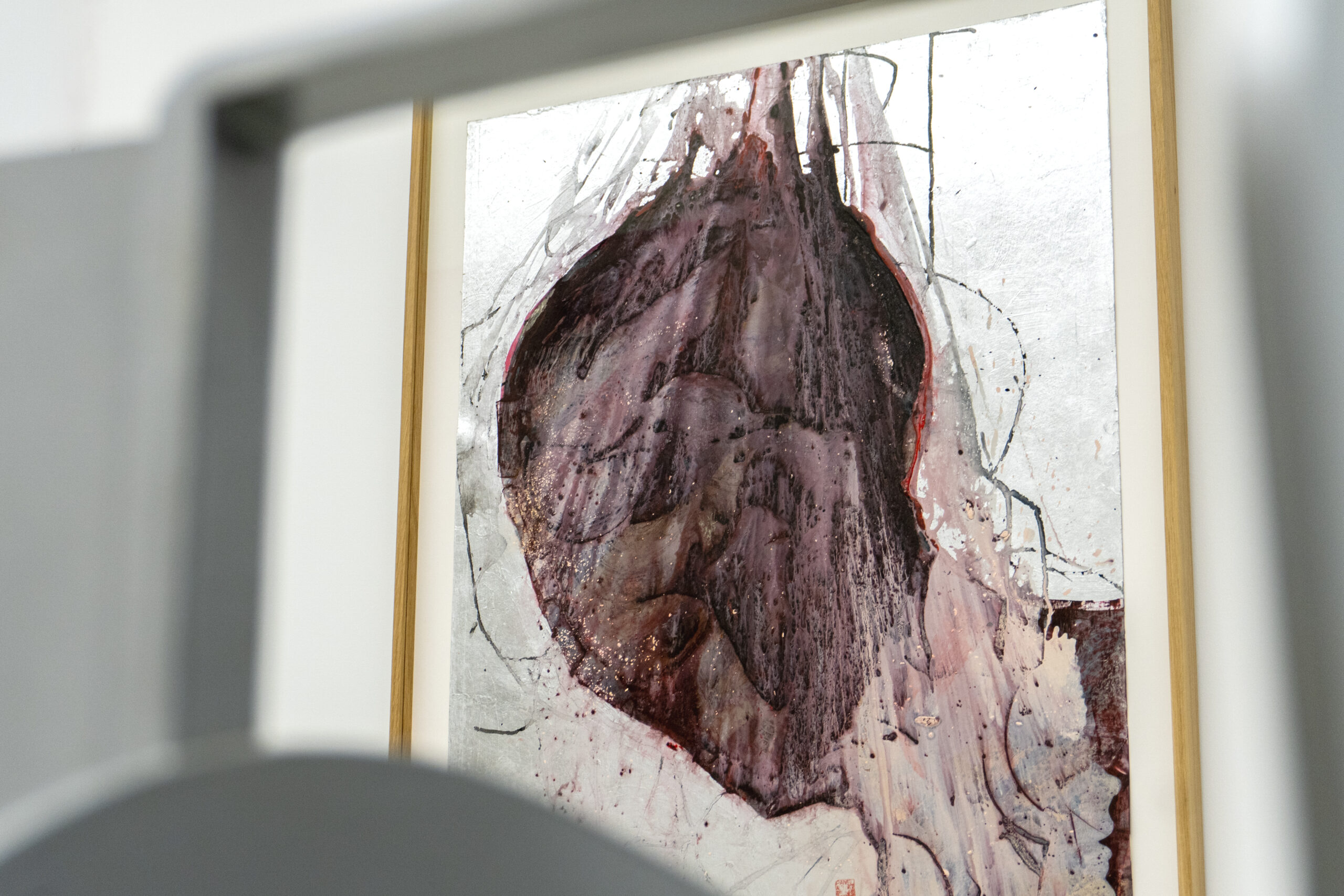

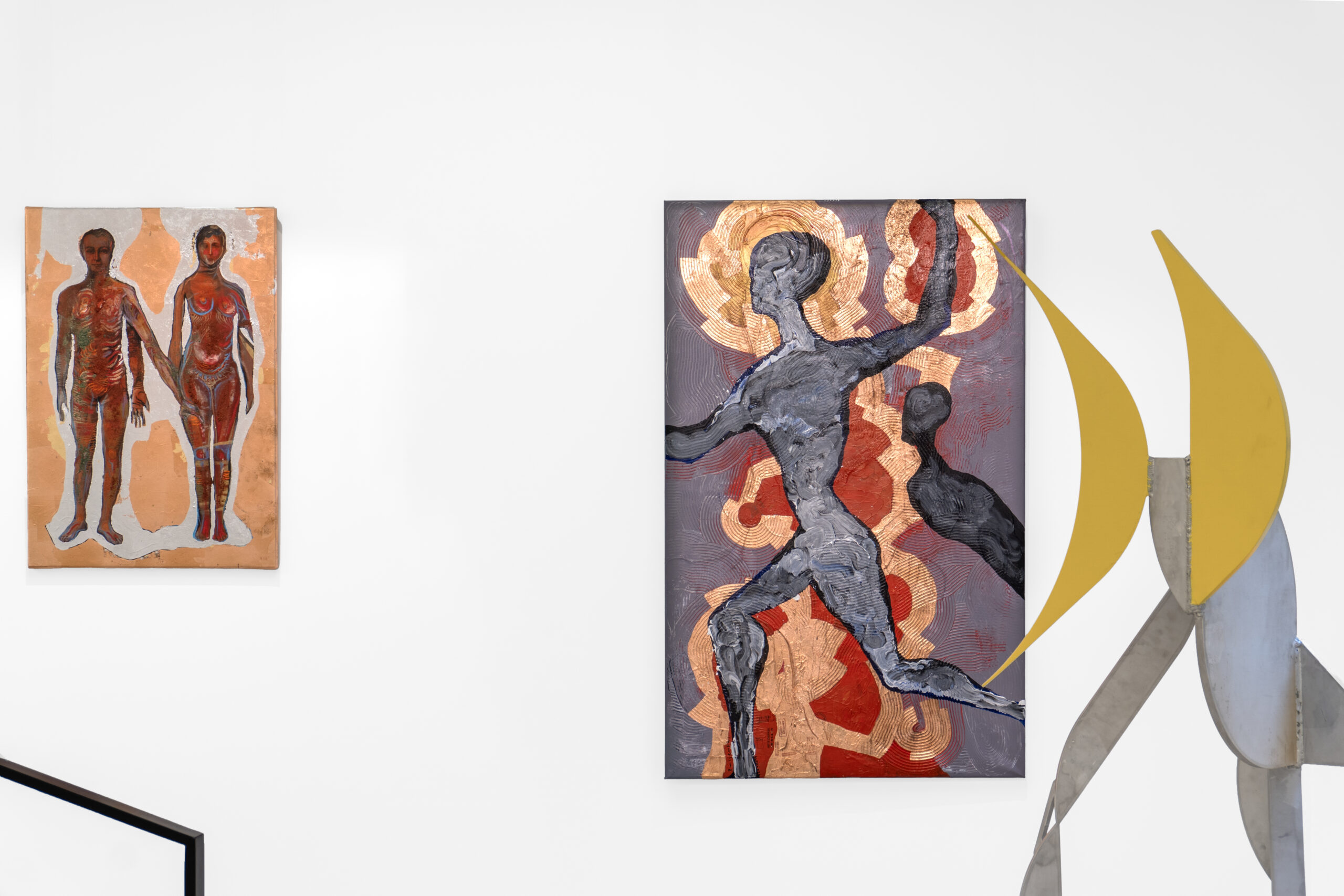

Ową siłę sklejania artyści aktywują przy pomocy tego, co wcześniej pocięli, rozdzielili i wydobyli z pierwotnego kontekstu, czyli na przykład z najróżniejszych książek, starych fotografii i czasopism czy plakatów wyborczych (zbieranych legalnie już po ogłoszeniu wyników – mimo że po tych twórcach spodziewałabym się akurat ciut więcej łobuzerki!). Na poszczególnych płaszczyznach pojawiają się twarze, ludzkie i zwierzęce sylwetki, fragmenty ciał, oczy, usta, czaszki, formy abstrakcyjne, nieregularne plamy. W kompozycji „Cukunft” dwie sfragmentaryzowane postaci biegną z prawa na lewo, jakby wbrew naszemu kulturowo wyćwiczonemu postrzeganiu kierunku poruszania się ku przyszłości. Wielokrotnie wszystko zaprawione jest farbą, czasem złotym, jakby ikonowym tłem, (nie)czytelnymi napisami oraz stemplami z sygnaturami Althamera i Żmijewskiego wykonanych w różnych alfabetach. Pieczątki, którymi twórcy zafascynowali się podczas wspólnego pobytu w Japonii, potwierdzają autentyczność i sygnują poszczególne dzieła, jednocześnie pozwalając artystom uchylić się od gestu ręcznego wstawiania podpisów.

Mówiąc krótko: dzieje się! Kompozycje są warstwowe niczym palimpsesty; czasem wręcz grubo i ekspresyjnie opracowane, jakby chciały nas skłonić do zadawania pytań, co zostało zakryte w trakcie procesu tworzenia, co bezpowrotnie zniknęło pod spodem, by na wierzchu mogła ostatecznie pojawić się inna forma. Kto i kiedy uznaje daną kompozycję za skończoną? – to przecież pytanie o poczucie władzy i decyzyjności, które nasuwa się wobec pracy w duecie, lecz na które nie znajdujemy odpowiedzi, patrząc na konkretne prace. Każdy z kolaży nosi w sobie ślady pracy czterech dłoni i dwóch osobowości, reagujących zarówno na otaczającą rzeczywistość, jak i na siebie wzajemnie – stąd ich kipiąca wizualna dynamika. Dla Didi-Hubermana kolaż i montaż są „układaniem różnic”: „Tym właśnie jest montaż: pokazujemy o tyle, ile rozdzielamy na części, nie ułożymy, o ile najpierw nie ‘rozłożymy’. Montujemy o tyle, o ile ukazujemy wejścia, ożywiające każdy temat w zetknięciu z innym”. Już sam kontakt i działania w duecie obu twórców to dla mnie „układanie (się) różnic”, prowadzące do ożywiania tematów i kreowania nowych znaczeń.

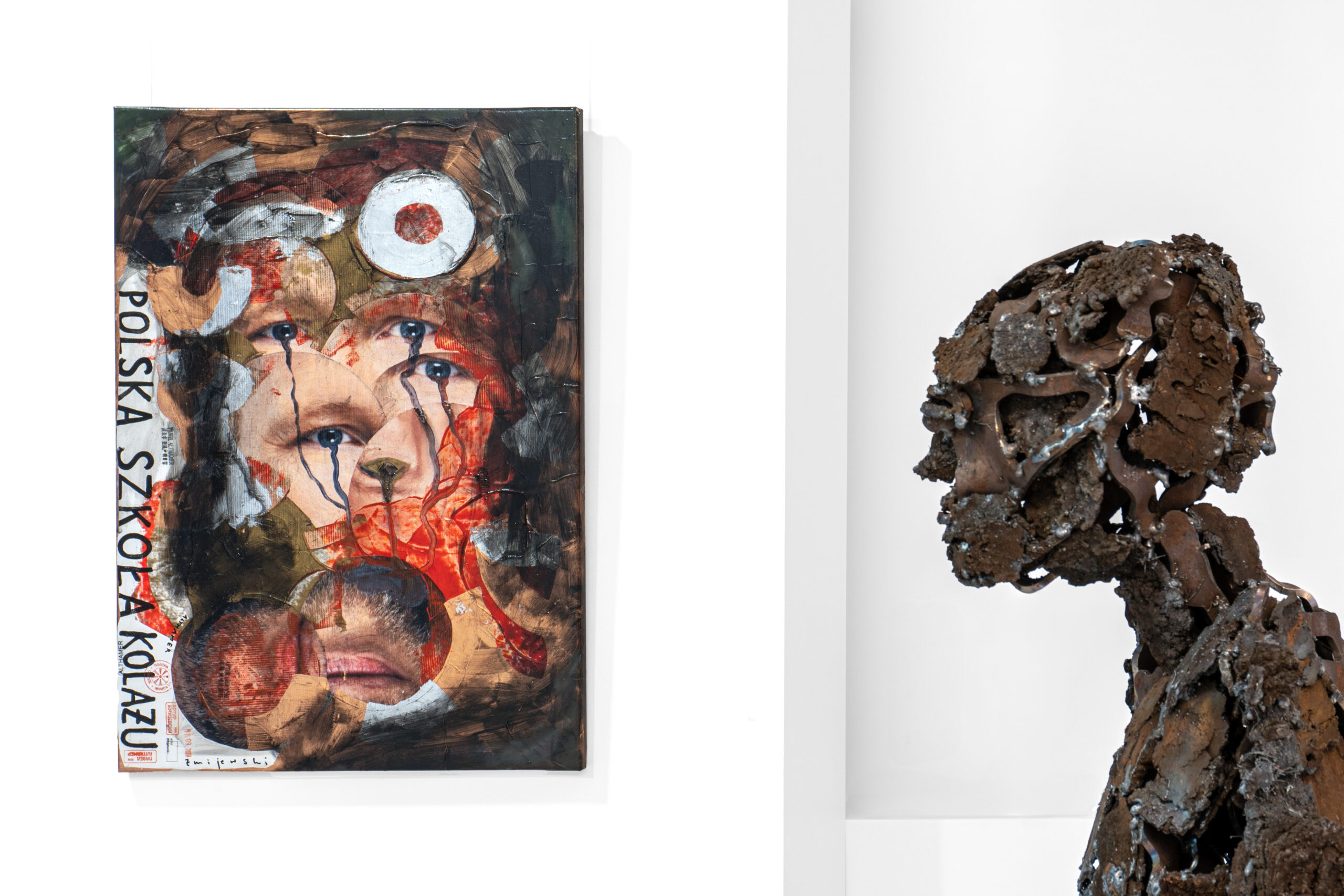

Tytuł cyklu wspólnie wykonanych prac „Polska szkoła kolażu” oraz jednocześnie wystawy w galerii SZOKART w Poznaniu wskazuje, że artyści biorą się za bary z mitem polskiej szkoły plakatu, a więc chcą stawać w szranki z mistrzami skondensowanych opowieści wizualnych, często zabarwionych politycznym przesłaniem. Ponadto Żmijewski to przecież pilny czytelnik francuskiego filozofa Jacquesa Rancièra, o którego koncepcji obrazu pisał następująco: Obraz „[m]ówi nam coś dopiero wtedy, gdy się o nim mówi, gdy zostaje złapany w siatkę dyskursu, gdy jest na przykład kolażem – dopiero nakładające się na siebie pasaże tekstów i fragmentów wizualności tworzą mówiące ‘obrazy, czyli związki między widzialnością a znaczeniem’.” Nieprzypadkowo owym przykładem jest właśnie kolaż, który ze swej medialno-technicznej natury jest wyjątkowo predestynowany do „mówienia” i kreowania znaczeń na bazie elementów wizualnych.

Althamer i Żmijewski tworzą wszak wspólnie obrazy o egzystencjalnej kondycji człowieka, złu, cierpieniu, ekstazie, emocjach, erotyce, także o frustracji, rozpadzie twarzy jako nośnika tożsamości człowieka. Ten ostatni aspekt szczególnie silnie uwidacznia się w serii bazującej na plakatach wyborczych, które twórcy poddali swego rodzaju „torturom”: wydzieraniu, wypalaniu, rozszarpywaniu czy przeciwnie – nawarstwianiu na siebie kolejnych oblicz jakby chcieli odebrać im indywidualność i podać w wątpliwość ich wyeksponowaną frontem do wyborców „szczerość”. Kwestia ta uwidacznia się w szczególnie wyrazisty sposób w pracach zatytułowanych „Wybrańcy”, „wybory.pl”, „Testament mój” i „Razem”. W symbolu twarzy nakładają się bowiem opozycje pomiędzy twarzą rozumianą jako „ikona” i twarzą rozumianą jako „fasada”, „obraz” czy „maska”. W dłoniach Althamera i Żmijewskiego twarze przekształcają się w maski, po-twarze, poddawane procesowi profanacji i pozbawione sakralnej aury. Oblicza stają się performatywne, edytowalne, w jakimś sensie przerażające, a wszystkie te zabiegi pozbawiają je wystudiowanego spokoju, przekonującego uśmiechu i wiarygodności ćwiczonej ze spin doktorami. Patrzą na nas z takich prac jak „Portret wielokrotny”, „Bez imienia”, „One”, „Oni”, „Ona”, „One”, „Kilku” czy „Kilkoro”, a tytuły wskazujące osoby, a jednak bezosobowe, jeszcze ich wydźwięk intensyfikują.

Napięcie, które staje się w tych kompozycjach silnie widoczne – między demontażem, separacją, a więc siłą analityczną kolażu a jego ponownym sklejeniem, siłą syntetyczną – wskazuje na fakt, że kolaż jako strategia Althamera i Żmijewskiego ma wymiar definitywnie krytyczny. Buduje nowe znaczenia na strzępach znaczeń rozdartych, zapraszając nas do refleksji nad tym, co ukryte pod pozornie spójną maską rzeczywistości.

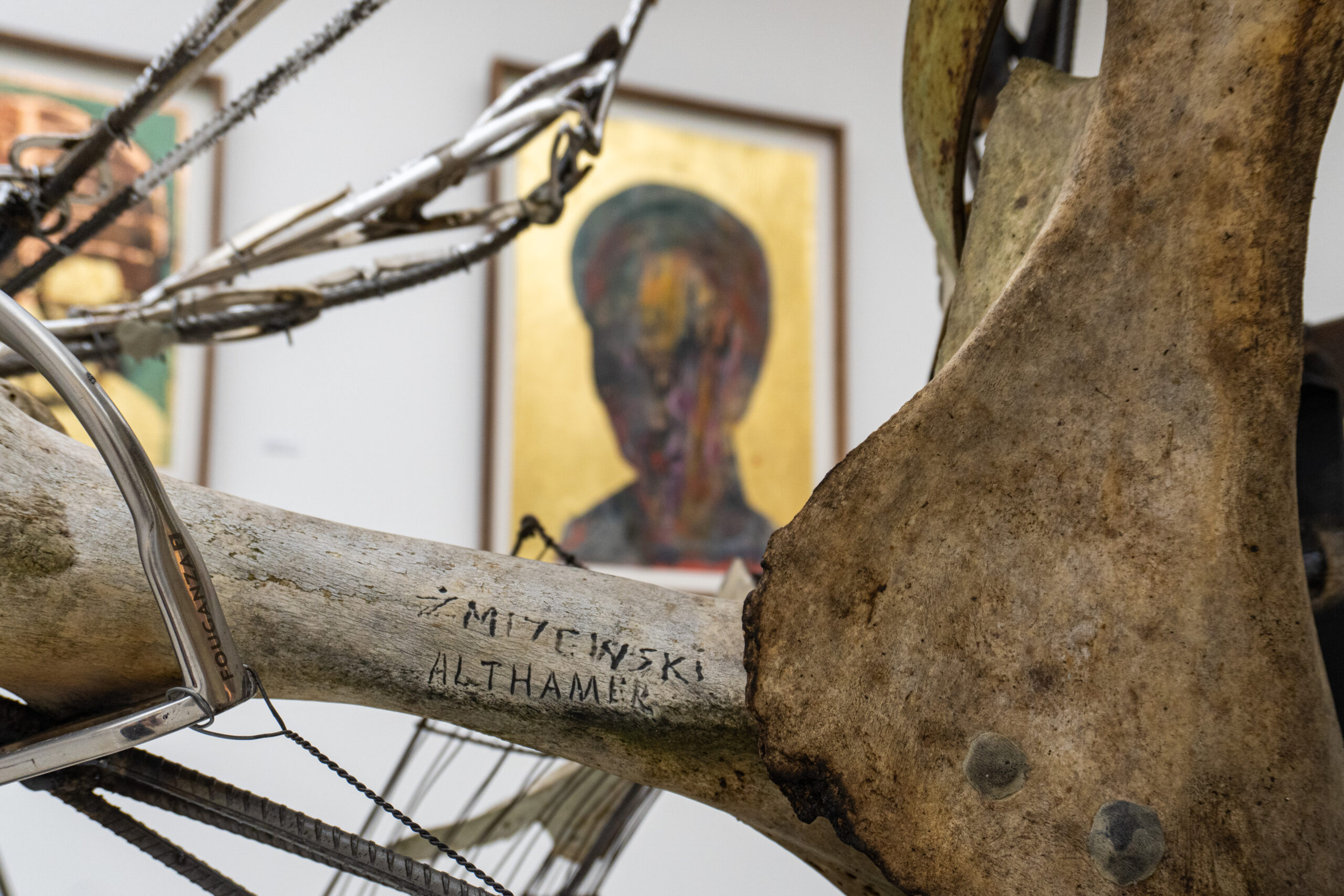

W podobnej zadumie tonie również postać, przedstawiona w rzeźbie przygotowanej specjalnie na wystawę w galerii SZOKART w Poznaniu. To kolaż, a może w zasadzie brikolaż, złożony m.in. z kości zwierząt znalezionych przez artystów w lesie, elementów metalowych, róży wiatrów, ortezy z siatki, narzędzi chirurgicznych, czaszki z brązu i afrykańskiej maski z muszlami. Czaszka z pustymi oczodołami zamiast twarzy „spogląda” w dół ku trzymanej w dłoniach masce jakby się w niej przeglądała jak w lustrze. Według francuskiego antropologa Claude’a Lévi-Straussa: ,,Bricoleur potrafi wykonać najróżniejsze zadania, jednakże, w odróżnieniu od inżyniera nie jest uzależniony od surowców i narzędzi obmyślanych i zdobywanych na miarę danego projektu. Świat narzędzi bricoleur’a jest zamknięty, a regułą gry jest zawsze posługiwanie się środkami będącymi pod ręką (…). Zatem zasobu środków, jakimi posługuje się bricoleur, nie może określać projekt (…), określa je jedynie instrumentalność”. Tak właśnie działają Althamer i Żmijewski, gdy tworzą swoje rzeźby, montując je z elementów, które znalazły się właśnie w ich zasięgu – tak jak chociażby kości odkryte w lesie w trakcie spaceru. Bricoleur jest figurą refleksyjną, a bricolage jawi się w tym kontekście jako strategia postępowania nie tylko artystycznego, lecz również badawczego, kreatywnego w relacji do zastanych treści kulturowych i krytycznego wobec nich.

Althamer i Żmijewski są zatem zbieraczami, którzy (bri)kolażują na pierwszy rzut oka niepasujące do siebie części, by odkryć przed nami te warstwy rzeczywistości, które nie zawsze dostrzegamy, oraz by wytrącić nas z utartych ścieżek postrzegania. Obaj twórcy „układają różnice” w taki sposób, że z ich kompozycji wyziera również poczucie humoru i ironiczne nastawienie zarówno do przetwarzanych motywów, jak i do własnych strategii artystycznych.

Marta Smolińska

The Polish school of collage:

Paweł Althamer and Artur Żmijewski and their arranging differences

‘How can one not see that only that which has first been separated, cut apart, will stick together [colle] with force? That only that which has first been in touch will separate and “cut through” [tranche] intensely?’ – thus the French philosopher and art historian Georges Didi-Huberman wrote about the uniqueness and potential of collage as a technique. When I look at the works made by the duo Paweł Althamer and Artur Żmijewski, I firmly believe that these two artists are not only very percipiently aware of these aspects, but also succeed in activating their innate character. I also think that in this particular context, the words ‘force’ and ‘intensity’ are of especial significance, because the two artists ‘rub up against’ and ‘wrangle with’ one another as they build each composition, negotiating space within them for the decisions they each want to take, or responding to each other gesture for gesture. The works that come into being on these sheets of paper and canvases, and the jointly made sculptures, are packed with tension and the processual energy recorded within them, which coruscates with traces of their personalities.

The two artists activate this sticking force using things that they had previously cut up, separated, and extracted from their original contexts, i.e., from various kinds of books, old photographs, magazines, or election posters (collected legally following the official announcement of the results – even though I would have expected somewhat more mischief from these particular two artists!). The various planes give glimpses of faces, human and animal figures, body parts, eyes, mouths, skulls, abstract forms, and irregular patches. In the composition entitled Cukunft, two fragmentary figures are running from right to left as if against the current of our culturally conditioned perception of movement toward the future. Everything is coated in several layers of paint, some of them gold, like the background of an icon, with (il)legible inscriptions, and stamps bearing Althamer and Żmijewski’s signatures in various alphabets. The stamps, which fascinated them during a trip they took to Japan, provide confirmation of the authenticity of the pieces, and function as signatures, while allowing the artists to sidestep the convention of signing their works manually.

In short: there is so much going on! The compositions are layered like palimpsests, sometimes thickly, and expressively designed, as if the intention were to goad us into asking what was covered up in the creative process, what disappeared irrevocably beneath the surface, ultimately giving way to a different form. Who deems a given composition finished, and at what point? – this is a question about the sense of authority and the power to take decisions, a question that must come up when working in tandem, but to which we find no answers as we view the works. Each collage bears the traces of the work of four hands and two personalities, both of which react to their environment and to each other, hence their effervescent visual dynamic. For Didi-Huberman, collage and montage are ‘arrangement of differences’: he defined montage as showing by splitting into parts, and never arranging before fully disassembling. He saw it as showing ‘ways in’ that enliven every subject in its contact with others. The very contact and cooperation of these two artists is for me an ‘arrangement of differences’ in itself, one that enlivens themes and creates new meanings.

The title of this group of jointly made works, The Polish School of Collage, which is also the title of the exhibition in SZOKART Gallery in Poznań, is an indication that the two artists are taking on the myth of the Polish school of poster art, and have the ambition to compete with its masters of visual, often politically tinged stories. Żmijewski is also an avid reader of the French philosopher Jacques Rancière, of whose conception of the image he has written thus: an image ‘speaks to us only when it is spoken about, when it is caught up in a network of discourse, when it is, for example, a collage – only overlapping passages of text and details of visuality create speaking “images, in other words, links between visibility and meaning”’. It is no coincidence that this ‘example’ is collage, which by the very nature of its medium and technique is uniquely predestined to ‘speak’ and to create meanings on the basis of its visual elements.

For Althamer and Żmijewski together create images that speak about the human existential condition, evil, suffering, ecstasy, emotions, eroticism, and about frustration, and the disintegration of the face as a medium of the human identity. Particular attention is drawn to this latter aspect in the series based on election posters, which the artists subjected to various forms of ‘tortures’, tearing pieces out of them, burning them, ripping them up, or, conversely, superimposing face after face upon each other as if trying to strip them of their individuality and cast doubt on the ‘genuine’ front that they were presenting to their electorate. This notion is foregrounded in the works entitled The Chosen Ones, elections.pl, My Testament, and Together: here, the symbol of the face is composed of the opposing concepts of the face as ‘icon’ and as ‘façade’, ‘image’, or ‘mask’. In Althamer and Żmijewski’s hands, faces become masks, post-faces, subjected to the process of profanation, and stripped of any sacral aura. These faces become performative, editable, and in a sense terrifying; all of these procedures strip them of their studied calm, their convincing smiles, and their credibility practised with their spin doctors. They look out at us from works such as Multiple Portrait, No Name, One, Them (m. pl.), Her, Them (f. pl.), A Few (m. pl.), and A Few (m./f. pl.), and their titles, which designate personae, yet are impersonal, intensify their tone further still.

The tension that is abundantly clear in these compositions – between deconstruction and separation, i.e. between the analytical power of the collage and the synthetic force of sticking back together – is an indication that collage as a strategy adopted by Althamer and Żmijewski has a definitively critical dimension. It builds new meanings on shreds of torn meanings, inviting us to reflect on what is hidden beneath the apparently cohesive mask of reality.

The sculpture made specially for the exhibition in SZOKART Gallery in Poznań portrays a figure lost in precisely this aura of contemplation. It is also a collage, or perhaps, more accurately, a bricolage, composed of elements including animal bones found by the artists in the woods, pieces of metal, compass roses, mesh orthopaedic braces, surgical instruments, bronze skulls, and an African mask decorated with shells. The skull, with empty eye sockets in place of a face, ‘looks’ down at the mask, which the figure holds in its hands, as if surveying itself in a mirror. In the words of the French anthropologist Claude Lévi-Strauss:

The bricoleur is adept at performing a large number of diverse tasks, but, unlike the engineer, he does not subordinate each one to the availability of raw materials and tools designed and acquired to fit his project. His universe of instruments is closed, and the rule of his game is always to make do with ‘whatever is at hand’ (…). Thus the bricoleur’s set of potentially usable elements cannot be defined by a project (…); it is defined solely by its instrumentality.

This is exactly how Althamer and Żmijewski make their sculptures: they assemble them from items they come across, such as the bones, which they found in a wood while on a walk. The bricoleur is a reflective figure, and bricolage in this context is not only an artistic strategy but also a creative, inquisitive, and also critical approach to pre-existing cultural content.

Thus Althamer and Żmijewski are gatherers, who (bri)collage using apparently incompatible elements to open up to us layers of reality that we do not always notice, and to jolt us out of conventional perceptive ruts. Both artists ‘arrange differences’ in such a way that their compositions also exude a sense of humour and an ironic attitude toward both the motifs that they process and their own artistic strategies.

Marta Smolińska

Polska szkoła kolażu:

Pawła Althamera i Artura Żmijewskiego układanie różnic

„Jak można nie widzieć, że tylko to, co najpierw zostało rozdzielone, rozcięte, będzie się sklejać z siłą? Że tylko to, co najpierw było w kontakcie, oddzieli się i ‘przetnie’ intensywnie?” – tak o wyjątkowości i potencjale techniki kolażu pisał francuski filozof i historyk sztuki Georges Didi-Huberman. Gdy patrzę na prace Pawła Althamera i Artura Żmijewskiego, wykonywane przez nich w duecie, jestem przekonana, że ci dwaj twórcy nie tylko bardzo przenikliwie dostrzegają te aspekty, lecz również potrafią uruchomić przyrodzony im charakter. Myślę również, że w tym konkretnym kontekście nie bez znaczenia pozostają słowa „siła” i „intensywność”, ponieważ obaj artyści „ścierają” i „siłują się” ze sobą, budując poszczególne kompozycje, negocjując w nich przestrzeń dla decyzji każdego z nich czy odpowiadając gestem na gest. Dzieła, powstające na papierach i płótnach, oraz wspólnie wykonane rzeźby są pełne napięcia i zapisanej w nich procesualnej energii, iskrzącej się śladami osobowości Althamera i Żmijewskiego.

Ową siłę sklejania artyści aktywują przy pomocy tego, co wcześniej pocięli, rozdzielili i wydobyli z pierwotnego kontekstu, czyli na przykład z najróżniejszych książek, starych fotografii i czasopism czy plakatów wyborczych (zbieranych legalnie już po ogłoszeniu wyników – mimo że po tych twórcach spodziewałabym się akurat ciut więcej łobuzerki!). Na poszczególnych płaszczyznach pojawiają się twarze, ludzkie i zwierzęce sylwetki, fragmenty ciał, oczy, usta, czaszki, formy abstrakcyjne, nieregularne plamy. W kompozycji „Cukunft” dwie sfragmentaryzowane postaci biegną z prawa na lewo, jakby wbrew naszemu kulturowo wyćwiczonemu postrzeganiu kierunku poruszania się ku przyszłości. Wielokrotnie wszystko zaprawione jest farbą, czasem złotym, jakby ikonowym tłem, (nie)czytelnymi napisami oraz stemplami z sygnaturami Althamera i Żmijewskiego wykonanych w różnych alfabetach. Pieczątki, którymi twórcy zafascynowali się podczas wspólnego pobytu w Japonii, potwierdzają autentyczność i sygnują poszczególne dzieła, jednocześnie pozwalając artystom uchylić się od gestu ręcznego wstawiania podpisów.

Mówiąc krótko: dzieje się! Kompozycje są warstwowe niczym palimpsesty; czasem wręcz grubo i ekspresyjnie opracowane, jakby chciały nas skłonić do zadawania pytań, co zostało zakryte w trakcie procesu tworzenia, co bezpowrotnie zniknęło pod spodem, by na wierzchu mogła ostatecznie pojawić się inna forma. Kto i kiedy uznaje daną kompozycję za skończoną? – to przecież pytanie o poczucie władzy i decyzyjności, które nasuwa się wobec pracy w duecie, lecz na które nie znajdujemy odpowiedzi, patrząc na konkretne prace. Każdy z kolaży nosi w sobie ślady pracy czterech dłoni i dwóch osobowości, reagujących zarówno na otaczającą rzeczywistość, jak i na siebie wzajemnie – stąd ich kipiąca wizualna dynamika. Dla Didi-Hubermana kolaż i montaż są „układaniem różnic”: „Tym właśnie jest montaż: pokazujemy o tyle, ile rozdzielamy na części, nie ułożymy, o ile najpierw nie ‘rozłożymy’. Montujemy o tyle, o ile ukazujemy wejścia, ożywiające każdy temat w zetknięciu z innym”. Już sam kontakt i działania w duecie obu twórców to dla mnie „układanie (się) różnic”, prowadzące do ożywiania tematów i kreowania nowych znaczeń.

Tytuł cyklu wspólnie wykonanych prac „Polska szkoła kolażu” oraz jednocześnie wystawy w galerii SZOKART w Poznaniu wskazuje, że artyści biorą się za bary z mitem polskiej szkoły plakatu, a więc chcą stawać w szranki z mistrzami skondensowanych opowieści wizualnych, często zabarwionych politycznym przesłaniem. Ponadto Żmijewski to przecież pilny czytelnik francuskiego filozofa Jacquesa Rancièra, o którego koncepcji obrazu pisał następująco: Obraz „[m]ówi nam coś dopiero wtedy, gdy się o nim mówi, gdy zostaje złapany w siatkę dyskursu, gdy jest na przykład kolażem – dopiero nakładające się na siebie pasaże tekstów i fragmentów wizualności tworzą mówiące ‘obrazy, czyli związki między widzialnością a znaczeniem’.” Nieprzypadkowo owym przykładem jest właśnie kolaż, który ze swej medialno-technicznej natury jest wyjątkowo predestynowany do „mówienia” i kreowania znaczeń na bazie elementów wizualnych.

Althamer i Żmijewski tworzą wszak wspólnie obrazy o egzystencjalnej kondycji człowieka, złu, cierpieniu, ekstazie, emocjach, erotyce, także o frustracji, rozpadzie twarzy jako nośnika tożsamości człowieka. Ten ostatni aspekt szczególnie silnie uwidacznia się w serii bazującej na plakatach wyborczych, które twórcy poddali swego rodzaju „torturom”: wydzieraniu, wypalaniu, rozszarpywaniu czy przeciwnie – nawarstwianiu na siebie kolejnych oblicz jakby chcieli odebrać im indywidualność i podać w wątpliwość ich wyeksponowaną frontem do wyborców „szczerość”. Kwestia ta uwidacznia się w szczególnie wyrazisty sposób w pracach zatytułowanych „Wybrańcy”, „wybory.pl”, „Testament mój” i „Razem”. W symbolu twarzy nakładają się bowiem opozycje pomiędzy twarzą rozumianą jako „ikona” i twarzą rozumianą jako „fasada”, „obraz” czy „maska”. W dłoniach Althamera i Żmijewskiego twarze przekształcają się w maski, po-twarze, poddawane procesowi profanacji i pozbawione sakralnej aury. Oblicza stają się performatywne, edytowalne, w jakimś sensie przerażające, a wszystkie te zabiegi pozbawiają je wystudiowanego spokoju, przekonującego uśmiechu i wiarygodności ćwiczonej ze spin doktorami. Patrzą na nas z takich prac jak „Portret wielokrotny”, „Bez imienia”, „One”, „Oni”, „Ona”, „One”, „Kilku” czy „Kilkoro”, a tytuły wskazujące osoby, a jednak bezosobowe, jeszcze ich wydźwięk intensyfikują.

Napięcie, które staje się w tych kompozycjach silnie widoczne – między demontażem, separacją, a więc siłą analityczną kolażu a jego ponownym sklejeniem, siłą syntetyczną – wskazuje na fakt, że kolaż jako strategia Althamera i Żmijewskiego ma wymiar definitywnie krytyczny. Buduje nowe znaczenia na strzępach znaczeń rozdartych, zapraszając nas do refleksji nad tym, co ukryte pod pozornie spójną maską rzeczywistości.

W podobnej zadumie tonie również postać, przedstawiona w rzeźbie przygotowanej specjalnie na wystawę w galerii SZOKART w Poznaniu. To kolaż, a może w zasadzie brikolaż, złożony m.in. z kości zwierząt znalezionych przez artystów w lesie, elementów metalowych, róży wiatrów, ortezy z siatki, narzędzi chirurgicznych, czaszki z brązu i afrykańskiej maski z muszlami. Czaszka z pustymi oczodołami zamiast twarzy „spogląda” w dół ku trzymanej w dłoniach masce jakby się w niej przeglądała jak w lustrze. Według francuskiego antropologa Claude’a Lévi-Straussa: ,,Bricoleur potrafi wykonać najróżniejsze zadania, jednakże, w odróżnieniu od inżyniera nie jest uzależniony od surowców i narzędzi obmyślanych i zdobywanych na miarę danego projektu. Świat narzędzi bricoleur’a jest zamknięty, a regułą gry jest zawsze posługiwanie się środkami będącymi pod ręką (…). Zatem zasobu środków, jakimi posługuje się bricoleur, nie może określać projekt (…), określa je jedynie instrumentalność”. Tak właśnie działają Althamer i Żmijewski, gdy tworzą swoje rzeźby, montując je z elementów, które znalazły się właśnie w ich zasięgu – tak jak chociażby kości odkryte w lesie w trakcie spaceru. Bricoleur jest figurą refleksyjną, a bricolage jawi się w tym kontekście jako strategia postępowania nie tylko artystycznego, lecz również badawczego, kreatywnego w relacji do zastanych treści kulturowych i krytycznego wobec nich.

Althamer i Żmijewski są zatem zbieraczami, którzy (bri)kolażują na pierwszy rzut oka niepasujące do siebie części, by odkryć przed nami te warstwy rzeczywistości, które nie zawsze dostrzegamy, oraz by wytrącić nas z utartych ścieżek postrzegania. Obaj twórcy „układają różnice” w taki sposób, że z ich kompozycji wyziera również poczucie humoru i ironiczne nastawienie zarówno do przetwarzanych motywów, jak i do własnych strategii artystycznych.

Marta Smolińska

ENG.

The Polish school of collage:

Paweł Althamer and Artur Żmijewski and their arranging differences

‘How can one not see that only that which has first been separated, cut apart, will stick together [colle] with force? That only that which has first been in touch will separate and “cut through” [tranche] intensely?’ – thus the French philosopher and art historian Georges Didi-Huberman wrote about the uniqueness and potential of collage as a technique. When I look at the works made by the duo Paweł Althamer and Artur Żmijewski, I firmly believe that these two artists are not only very percipiently aware of these aspects, but also succeed in activating their innate character. I also think that in this particular context, the words ‘force’ and ‘intensity’ are of especial significance, because the two artists ‘rub up against’ and ‘wrangle with’ one another as they build each composition, negotiating space within them for the decisions they each want to take, or responding to each other gesture for gesture. The works that come into being on these sheets of paper and canvases, and the jointly made sculptures, are packed with tension and the processual energy recorded within them, which coruscates with traces of their personalities.

The two artists activate this sticking force using things that they had previously cut up, separated, and extracted from their original contexts, i.e., from various kinds of books, old photographs, magazines, or election posters (collected legally following the official announcement of the results – even though I would have expected somewhat more mischief from these particular two artists!). The various planes give glimpses of faces, human and animal figures, body parts, eyes, mouths, skulls, abstract forms, and irregular patches. In the composition entitled Cukunft, two fragmentary figures are running from right to left as if against the current of our culturally conditioned perception of movement toward the future. Everything is coated in several layers of paint, some of them gold, like the background of an icon, with (il)legible inscriptions, and stamps bearing Althamer and Żmijewski’s signatures in various alphabets. The stamps, which fascinated them during a trip they took to Japan, provide confirmation of the authenticity of the pieces, and function as signatures, while allowing the artists to sidestep the convention of signing their works manually.

In short: there is so much going on! The compositions are layered like palimpsests, sometimes thickly, and expressively designed, as if the intention were to goad us into asking what was covered up in the creative process, what disappeared irrevocably beneath the surface, ultimately giving way to a different form. Who deems a given composition finished, and at what point? – this is a question about the sense of authority and the power to take decisions, a question that must come up when working in tandem, but to which we find no answers as we view the works. Each collage bears the traces of the work of four hands and two personalities, both of which react to their environment and to each other, hence their effervescent visual dynamic. For Didi-Huberman, collage and montage are ‘arrangement of differences’: he defined montage as showing by splitting into parts, and never arranging before fully disassembling. He saw it as showing ‘ways in’ that enliven every subject in its contact with others. The very contact and cooperation of these two artists is for me an ‘arrangement of differences’ in itself, one that enlivens themes and creates new meanings.

The title of this group of jointly made works, The Polish School of Collage, which is also the title of the exhibition in SZOKART Gallery in Poznań, is an indication that the two artists are taking on the myth of the Polish school of poster art, and have the ambition to compete with its masters of visual, often politically tinged stories. Żmijewski is also an avid reader of the French philosopher Jacques Rancière, of whose conception of the image he has written thus: an image ‘speaks to us only when it is spoken about, when it is caught up in a network of discourse, when it is, for example, a collage – only overlapping passages of text and details of visuality create speaking “images, in other words, links between visibility and meaning”’. It is no coincidence that this ‘example’ is collage, which by the very nature of its medium and technique is uniquely predestined to ‘speak’ and to create meanings on the basis of its visual elements.

For Althamer and Żmijewski together create images that speak about the human existential condition, evil, suffering, ecstasy, emotions, eroticism, and about frustration, and the disintegration of the face as a medium of the human identity. Particular attention is drawn to this latter aspect in the series based on election posters, which the artists subjected to various forms of ‘tortures’, tearing pieces out of them, burning them, ripping them up, or, conversely, superimposing face after face upon each other as if trying to strip them of their individuality and cast doubt on the ‘genuine’ front that they were presenting to their electorate. This notion is foregrounded in the works entitled The Chosen Ones, elections.pl, My Testament, and Together: here, the symbol of the face is composed of the opposing concepts of the face as ‘icon’ and as ‘façade’, ‘image’, or ‘mask’. In Althamer and Żmijewski’s hands, faces become masks, post-faces, subjected to the process of profanation, and stripped of any sacral aura. These faces become performative, editable, and in a sense terrifying; all of these procedures strip them of their studied calm, their convincing smiles, and their credibility practised with their spin doctors. They look out at us from works such as Multiple Portrait, No Name, One, Them (m. pl.), Her, Them (f. pl.), A Few (m. pl.), and A Few (m./f. pl.), and their titles, which designate personae, yet are impersonal, intensify their tone further still.

The tension that is abundantly clear in these compositions – between deconstruction and separation, i.e. between the analytical power of the collage and the synthetic force of sticking back together – is an indication that collage as a strategy adopted by Althamer and Żmijewski has a definitively critical dimension. It builds new meanings on shreds of torn meanings, inviting us to reflect on what is hidden beneath the apparently cohesive mask of reality.

The sculpture made specially for the exhibition in SZOKART Gallery in Poznań portrays a figure lost in precisely this aura of contemplation. It is also a collage, or perhaps, more accurately, a bricolage, composed of elements including animal bones found by the artists in the woods, pieces of metal, compass roses, mesh orthopaedic braces, surgical instruments, bronze skulls, and an African mask decorated with shells. The skull, with empty eye sockets in place of a face, ‘looks’ down at the mask, which the figure holds in its hands, as if surveying itself in a mirror. In the words of the French anthropologist Claude Lévi-Strauss:

The bricoleur is adept at performing a large number of diverse tasks, but, unlike the engineer, he does not subordinate each one to the availability of raw materials and tools designed and acquired to fit his project. His universe of instruments is closed, and the rule of his game is always to make do with ‘whatever is at hand’ (…). Thus the bricoleur’s set of potentially usable elements cannot be defined by a project (…); it is defined solely by its instrumentality.

This is exactly how Althamer and Żmijewski make their sculptures: they assemble them from items they come across, such as the bones, which they found in a wood while on a walk. The bricoleur is a reflective figure, and bricolage in this context is not only an artistic strategy but also a creative, inquisitive, and also critical approach to pre-existing cultural content.

Thus Althamer and Żmijewski are gatherers, who (bri)collage using apparently incompatible elements to open up to us layers of reality that we do not always notice, and to jolt us out of conventional perceptive ruts. Both artists ‘arrange differences’ in such a way that their compositions also exude a sense of humour and an ironic attitude toward both the motifs that they process and their own artistic strategies.

Marta Smolińska